About the Pawnee Indian Tribe

All the Plains Indians were rovers, buffalo hunters, and warriors; none of them were bolder or braver than the Pawnee. This tribal name is more frequently spelled Pawnee. The tribe belonged to the Caddoan family, which includes also the Caddoes and Wichitas and perhaps the Lipans and Tonkaways. The Pani were formerly numerous and occupied a large district in Nebraska. To-day they are few, and rapidly diminishing. In 1885 they numbered one thousand forty-five; in 1886, nine hundred ninety-eight; in 1888, nine hundred eighteen; in 1889, eight hundred sixty-nine. To-day they live upon a reservation in Oklahoma.

It is believed that the Pawnee came from the south, perhaps from some part of Mexico. They appear first to have gone to some portion of what is now Louisiana; later they migrated northward to the district where the whites first knew them. The name Pawnee means wolves, and the sign language name for the Pani consists of a representation of the ears of a wolf. Several reasons have been given for their bearing this name. Perhaps it was because they were as tireless and enduring as wolves; or it may be because they were skillful scouts, trailers, and hunters. They were in the habit of imitating wolves in order to get near camp for stealing horses. They threw wolfskins over themselves and crept cautiously near. Wolves were too common to attract much attention.

In the olden time the Pani hunted the buffalo on foot. Choosing a quiet day, so that the wind might not bear their scent to the herd, the hunters in a long line began to surround a little group of grazing buffalo. Some of the men were dressed in wolfskins, and crept along on all fours. When a circle had been formed around the animals, the hunters began to close in. Presently one man shouted and shook his blanket to scare the buffalo nearest him. The others did the same, and in a short time the excited herd was running blindly, turning now here and now there, but always terrified by one or another of the men in the now ever smaller circle. Finally the animals were tired out with their running and were shot and killed.

The way in which the Pawnee used to make pottery vessels was simple and crude. The end of a tree stump was smoothed for a mold. Clay was mixed with burnt and pounded stone, to give it a good texture, and was then molded over this. The bowl when dry was lifted off and baked in the fire. Sometimes, instead of thus shaping bowls, they made a framework of twigs which was lined with clay, and then burnt off, leaving the lining as a baked vessel.

As long as they have been known to the Whites, the Pawnee have been an agricultural people. They raised corn, beans, pumpkins, and squashes, which they said Tirawa himself, whom they most worshiped, gave them. Corn was sacred, and they had ceremonials connected with it, and called it “mother.” In cultivating their fields they used hoes made of bone: these were made by firmly fastening the shoulder-blade of a buffalo to the end of a stick.

Two practices in which the Pawnee differed from most Plains Indians remind us of some Mexican tribes: they kept a sort of servants and sacrificed human beings. Young men or boys who were growing up often attached themselves to men of importance. They lived in their houses and received support from them: in return, they drove in and saddled the horses, made the fire, ran errands, and made themselves useful in all possible ways.

The sacrifice of a human being to Tirawa—and formerly to the morning star—was made by one band of the Pawnee. When captives of war were taken, all but one were adopted into the tribe. That one was set apart for sacrifice. He was selected for his beauty and strength. He was kept by himself, fed on the best of everything, and treated most kindly.

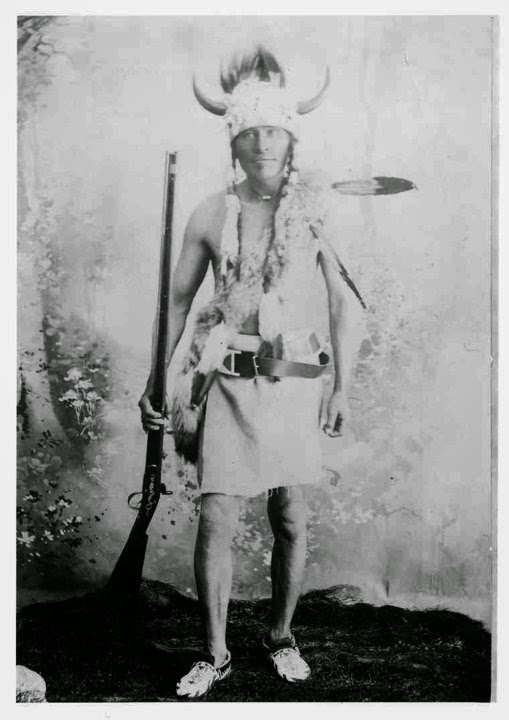

Pawnee human sacrifice to the morning star

Before the day fixed for the sacrifice, the people danced four nights and feasted four days. Each woman, as she rose from eating, said to the captive: “I have finished eating, and I hope I may be blessed from Tirawa; that he may take pity on me; that when I put my seeds in the ground they may grow, and that I may have plenty of everything.” You must remember that this sacrifice was not a merely cruel act, but was done as a gift to Tirawa, that he might give good crops to the people. On the last night, bows and arrows were prepared for every man and boy in the village, even for the very little boys; every woman had ready a lance or stick. By daybreak the whole village was assembled at the western end of the town, where two stout posts with four cross-poles had been set up. To this framework the captive was tied. A fire was built below, and then the warrior who had captured the victim shot him through with an arrow. The body was then shot full of arrows by all the rest. These arrows were then removed, and the dead man's breast was opened and blood removed. All present touched the body, after which it was consumed by the fire, while the people prayed to Tirawa, and put their hands in the smoke of the fire, and hoped for success in war, and health, and good crops.

Almost all these facts about the Pawneeare from Mr. Grinnell's book. I shall quote from him now the story of Crooked Hand. He was a famous warrior. On one occasion the village had gone on a buffalo hunt, and no one was left behind except some sick, the old men, and a few boys, women, and children. Crooked Hand was among the sick. The Sioux planned to attack the town and destroy all who had been left behind. Six hundred of their warriors in all their display rode down openly to secure their expected easy victory. The town was in a panic. But when the news was brought to Crooked Hand lying sick in his lodge, he forgot his illness and, rising, gave forth his orders.

They were promptly obeyed. “The village must fight. Tottering old men, whose sinews were now too feeble to bend the bow, seized their long-disused arms and clambered on their

horses. Boys too young to hunt grasped the weapons that they had as yet used only on rabbits and ground squirrels, flung themselves on their ponies, and rode with the old men. Even squaws, taking what weapons they could,—axes, hoes, mauls, pestles,—mounted horses and marshaled themselves for battle. The force for the defense numbered two hundred superannuated old men, boys, and women. Among them all were not, perhaps, ten active warriors, and these had just risen from sick-beds to take their place in the line of battle.

horses. Boys too young to hunt grasped the weapons that they had as yet used only on rabbits and ground squirrels, flung themselves on their ponies, and rode with the old men. Even squaws, taking what weapons they could,—axes, hoes, mauls, pestles,—mounted horses and marshaled themselves for battle. The force for the defense numbered two hundred superannuated old men, boys, and women. Among them all were not, perhaps, ten active warriors, and these had just risen from sick-beds to take their place in the line of battle.

“As the Pawnees passed out of the village into the plain, the Sioux saw for the first time the force they had to meet. They laughed in derision, calling out bitter jibes, and telling what they would do when they had made the charge; and, as Crooked Hand heard their laughter, he smiled too, but not mirthfully.

“The battle began. It seemed like an unequal fight. Surely one charge would be enough to overthrow this motley Pawnee throng, who had ventured out to try to oppose the triumphal march of the Sioux. But it was not ended so quickly. The fight began about the middle of the morning; and, to the amazement of the Sioux, these old men with shrunken shanks and piping voices, these children with their small, white teeth and soft, round limbs, these women clad in skirts and armed with hoes, held the invaders where they were: they could make no advance. A little later it became evident that the Pawnees were driving the Sioux back. Presently this backward movement became a retreat, the retreat a rout, the rout a wild panic. Then indeed the Pawnees made a great killing of their enemies. Crooked Hand, with his own hand, killed six of the Sioux, and had three horses shot under him. His wounds were many, but he laughed at them. He was content; he had saved the village.”

From 1864 until 1876 the famous Pawnee scouts served our government faithfully. Those years were terrible on the Plains. White settlers were pressing westward. The Indians were desperate over the encroachments of the newcomers. Troubles constantly occurred between the pioneers and the Indians. During that sad and unsettled time, Lieutenant North and his Pani scouts served as a police to keep order and to punish violence.