Yuma Indian Facts

The valley of the Colorado River in Arizona, the peninsula of California and portions of the eastern shore of the Gulf of California, formed the home of the Yuma stock. They were found in these regions by Coronado as early as 1540, and own no traditions of having lived anywhere else. The considerable differences in their dialects within this comparatively small area indicates that a long period has elapsed since the stock settled in this locality and split up into hostile fractions.

It has also been called the Katchan or Cuchan stock, and the Apache, that being the Yuma word for “fighting men”; but we should confine the term Apaches to the Tinneh (Athapascan) tribe so

called, and to avoid confusion I shall dismiss the terms Apache-Yumas, Apache-Tontos and Apache-Mohaves, employed by some writers. The Yumas, from whom the stock derives its name, lived near the mouth of the Colorado River. Above them, on both banks of the river, were the Mohaves, and further up, principally on Virgin River, were the Yavapai.

called, and to avoid confusion I shall dismiss the terms Apache-Yumas, Apache-Tontos and Apache-Mohaves, employed by some writers. The Yumas, from whom the stock derives its name, lived near the mouth of the Colorado River. Above them, on both banks of the river, were the Mohaves, and further up, principally on Virgin River, were the Yavapai.

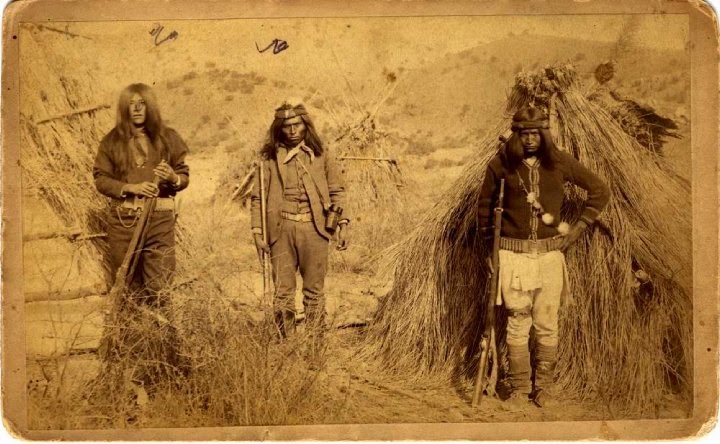

Most of the Yumas are of good stature, the adult males averaging five feet nine inches high, well built and vigorous. The color varies from a dark to a light mahogany; the hair is straight and coarse, the eyes horizontal, the mouth large, and the lips heavy. The skull is generally brachycephalic, but there are a number of cases of extreme dolichocephaly .

Animal totems with descent in the male line prevailed among the Yumas, though they seem for a long time not to have regarded these matters closely. In culture they vary considerably. The Seris or Ceris, who formerly lived in the hills near Horcasitas, but in 1779 were removed to the island of Tiburon, are described as thieves and vagrants, lazy and wretched. They were exceedingly troublesome to the Mexican government, having revolted over forty times. The boats they use are of a peculiar construction, consisting of rushes tied together. As weapons up to recent years they preferred the bow and arrow, and upon the arrow laid some kind of poison which prevented the wounds from healing.

Their dialect, which is harsh, is related especially to the western branch of the Yuma stem. They are described as light in color and some of them good-looking, but filthy in habits.

Their dialect, which is harsh, is related especially to the western branch of the Yuma stem. They are described as light in color and some of them good-looking, but filthy in habits.

The Yumas and Maricopas were agricultural, cultivating large fields of corn and beans, and irrigating their plantations by trenches. It is highly probable that formerly some of them dwelt in adobe houses of the pueblo character, and were the authors of some of the numerous ruined structures seen in southern Arizona. The pottery and basket work turned out by their women are superior in style and finish. A few years ago the Mohaves of the west bank lived in holes in the earth covered with brush, or in small wattled conical huts. For clothing they wore strips of cottonwood bark, or knotted grass. Tattooing and painting the person in divers colors were common. The favorite ornament was shells, arranged on strings, or engraved and suspended to the neck. The chiefs wore elaborate feather head-dresses.

The Tontos, so-called from their reputation for stupidity, are largely mixed with Tinné blood, their women having been captured from the Apaches. Though savage, they are by no means dull, and are considered uncommonly adept thieves.

Quite to the south, in the mountains of Oaxaca and Guerrero, the Tequistlatecas, usually known by the

meaningless term Chontales, belong to this stem, judging from the imperfect vocabularies which have been published.

meaningless term Chontales, belong to this stem, judging from the imperfect vocabularies which have been published.

The peninsula of California was inhabited by several Yuma tribes differing in dialect but much alike in culture, all being on its lowest stage. Wholly unacquainted with metals, without agriculture of any kind, naked, and constructing no sort of permanent shelters, they depended on fishing, hunting and natural products for subsistence. Their weapons were the bow and the lance, which they pointed with sharpened stones. Canoes were unknown, and what little they did in navigation was upon rafts of reeds and brush.

Marriages among them were by individual preference, and are said not to have respected the limits of consanguinity; but this is doubtful, as we are also told that the mother-in-law was treated with peculiar ceremony. Their rites for the dead indicate a belief in the survival of the individual. The body was buried and after a certain time the bones were cleaned, painted red, and preserved in ossuaries.

The population was sparse, probably not more than ten thousand on the whole peninsula. At the extreme south were the Pericus, who extended to N. Lat. 24°; beyond these lived the Guaicurus to about Lat. 26°; and in the northern portion of the peninsula to latitude 33° the Cochimis. The early writers state that in appearance these bands did not differ from the Mexicans on the other side of the Gulf.

Their skulls, however, which have been collected principally from the district of the Pericus, present a peculiar degree of elongation and height (dolichocephalic and hypsistenocephalic).

Their skulls, however, which have been collected principally from the district of the Pericus, present a peculiar degree of elongation and height (dolichocephalic and hypsistenocephalic).

YUMA LINGUISTIC STOCK.

- Ceris, on Tiburon Island and the adjacent coast.

- Cochimis, northern portion of Californian peninsula.

- Cocopas, at mouth of Colorado river.

- Coco-Maricopas, on middle Gila river.

- Comeyas, between lower Colorado and the Pacific.

- Coninos, on Cataract creek, branch of the Colorado.

- Cuchanes, see Yumas.

- Diegueños, near San Diego on the Pacific.

- Gohunes, on Rio Salado and Rio Verde.

- Guaicurus, middle portion of Californian peninsula.

- Hualapais, from lower Colorado to Black Mountains.

- Maricopas, see Coco-Maricopas.

- Mohaves, on both banks of lower Colorado.

- Pericus, southern extremity of Californian peninsula.

- Tontos, in Tonto basin and in the Pinal mountains.

- Tequistlatecas, of Oaxaca and Guerrero.

- Yavipais, west of Prescott, Arizona.

- Yumas, near mouth of Colorado river.