Nowhere among American Indians are more languages found in a smaller space than in California. Those spoken near the Coast, within the area of the Missions, appear to belong to at least nine language families or stocks. In Powell's map the state looks like a piece of patchwork, so many are the bits of color, which represent different languages. These Coast Indians of California were ugly to see. They were of medium stature, awkwardly shaped, with scrawny limbs; they had dull faces, with fat and round noses, and looked much like negroes, only their hair was straight. In disposition they were said to be sluggish, indolent, cowardly, and unenterprising. Some tribes in the interior were better, but none of the California Indians seem to have presented a high physical type or much comfort in life.

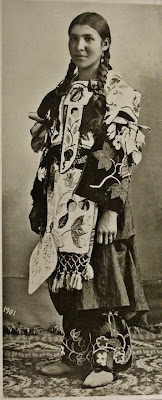

1899 Photo of a Coahuilla Indian woman We shall say little about the life and customs of the California Indians, and what we do say will be chiefly about the Coahuilla tribe. These Indians live in the beautiful high Coahuilla Valley in Southern California. Formerly at least part of the tribe were “Mission Indians.” Some of them were connected with the San Gabriel Mission near the present city of Los Angeles. They appear to present a better type than many of the Mission Indians, being larger, better built, and stronger. Ramona, who was the heroine of Helen Hunt Jackson's story, is a Coahuilla Indian, still living. If she ever was beautiful, it must have been long ago, although she is not an old woman. These Indians live in little houses, largely built of brush, scattered over the valley. They have some ponies and cattle, and cultivate some ground. Near every house, perched upon big boulders, are quaint little structures made of woven willows and like big beehives in form; they are granaries for stowing away acorns or grain.

Granary at Coahuilla. (From Photograph.)

Acorns are much used by California Indians. They are bitter and need to be sweetened. They are first pounded to a meal or flour. A wide basket is filled with sand, which is carefully scooped away so as to leave a basin-shaped surface; the acorn meal is spread upon this, and water is poured upon it. The bitterness is soaked out, and the meal left sweet and good.

Coiled Baskets: California. (From Photograph.)

A fine art among most Californian tribes is the making of baskets. Those made at Coahuilla are mostly what is known as “coiled work.” A bunch of fine, slender grass is taken and treated as if it were a rope. It is coiled around and around in a close coil. Long strips of reed grass are then taken and wrapped like a thread around the coiled rope, sewing the coil at each wrapping to the next coil. In this way the foundation coiled rope of grass is entirely covered and concealed by the wrapping of reed grass, and at the same time firmly united. By using differently colored strips of the reed grass, patterns are worked in. Horses, men, geometrical patterns, and letters are common. Among some Californian tribes such baskets were covered with brilliant feathers, which were woven in during the making.

Cahuilla Indian shelter on the Colorado River

Among the delicacies of some south Californian tribes was roasted mescal. Mescal is a plant of the desert, with great, pointed, fleshy leaves. At the proper time it throws up a huge flower-stalk, which bears great numbers of flowers. Mr. Lummis describes the roasting of its leaves and stalks: “A pit was dug, and a fire of the greasewood's crackling roots kept up therein until the surroundings were well heated. Upon the hot stones of the pit was laid a layer of the pulpiest sections of the mescal; upon this a layer of wet grass; then another layer of mescal, and another of grass, and so on. Finally the whole pile was banked over with earth. The roasting—or, rather, steaming—takes from two to four days.... When he banks the pile with earth, he arranges a few long bayonets of the mescal so that their tips shall project. When it seems to him that the roast should be done, he withdraws one of these plugs. If the lower end is well done, he uncovers the heap and proceeds to feast; if still too rare, he possesses his soul in patience until a later experiment proves the baking.”This method of roasting mescal is about the same pursued farther north with camas root.

A gambling game common among Californian tribes is called by the Spanish name peon. It is very similar to a game played in many other parts of the United States by many Indian tribes. It consists simply of guessing in which of two hands the marked one of two sticks or objects is held. The game is played by two parties, one of which has the sticks, while the other guesses. Each success is marked by a stick or counter for the winner, and ten counts make a game. Among the Coahuillas there are four persons on a side. Songs are sung, which become loud and wild; at times the players break into fierce barking. Then the guess is made. Great excitement arises, which grows wilder and wilder toward the end of a close game. Violent movements and gestures are made to deceive the carefully watching guessers. Sometimes men will bet on this game the last things they own, even down to the clothes they wear.

Mr. Barrows, who has described the game of peon tells of the bird dances of the Coahuillas. These Indians highly regard certain birds. Of all, the eagle is chief. In the eagle dance the dancer wears a breech-clout; his face, body, and limbs are painted in red, black, and white; his dance skirt and dance bonnet are made of eagle feathers. In his dancing and whirling he imitates the circling and movements of the eagle. At times he whirls about the great circle of spectators so rapidly that his feather skirt stands up straight below his arms. The music of this dance is so old that the words are not understood even by the singers.

Santa Barbara, California. (From Photograph.)

They took possession in 1697 and built a Mission at San Dionisio, in Lower California. By 1745, they had fourteen Missions established, all in what is now Lower California. The Jesuits gave way to the Franciscan monks, and these began in 1769 their first Mission in California proper, at San Diego. One after another was added, until, in 1823, there were twenty-one Franciscan Missions, stretching from San Diego to San Francisco. Each mission had a piece of ground fifteen miles square. The center of the Mission was the church, with cloisters where the monks lived. The houses of the Indian converts—which were little huts—were grouped together about the church, arranged in rows. Unmarried men were housed in a separate building or buildings, as were young women also. During the sixty-five years of these Missions about seventy-nine thousand converts were made. Every one at these Missions was busy. The men kept the flocks and herds, sheared the sheep, and cared for the fields and vines. Women cared for the houses and the church. There was spinning, weaving, leather work, and plenty else to be done. Still the Indians were not hard worked, and they ought to have been happy. Their time was regularly planned out for them. At sunrise all rose and went to mass; soon after mass breakfast was ready and sent to the houses in baskets; then every one worked. At noon dinner was sent around again from house to house; then came the afternoon work. After evening mass, there was a supper of sweet gruel. There was a good deal of time left after the services and work were through. The monks allowed the Indians to keep up their native dances and amusements so far as they believed them harmless.

Some persons seem to think that the monks made slaves of the Indians. Rather they considered them children, who needed oversight, direction, and sometimes punishment. However, the Indians were probably better dressed and housed and fed than ever before, and, perhaps, happier. But the Missions are now past. Their twenty-one old churches still stand,—our most interesting historical relics,—but the Indian converts have scattered, and in time they will forget, if they have not already forgotten, that they or their people were ever Mission Indians.

.png)