OTTAWA AND CHIPPEWA INDIAN HISTORY OF MICHIGAN

I have seen a number of writings by different men who attempted to give an account of the Indians who formerly occupied the Straits of Mackinac and Mackinac Island, (that historic little island which stands at the entrance of the strait,) also giving an account of the Indians who lived and are yet living in Michigan, scattered through the counties of Emmet, Cheboygan, Charlevoix, Antrim, Grand Traverse, and in the region of Thunder Bay, on the west shore of Lake Huron. But I see no very correct account of the Ottawa and Chippewa tribes of Indians, according to our knowledge of ourselves, past and present. Many points are far from being credible. They are either misstated by persons who were not versed in the traditions of these Indians, or exaggerated. An instance of this is found in the history of the life of Pontiac (pronounced Bwon-diac), the Odjebwe (or Chippewa) chief of St. Clair, the instigator of the massacre of the old fort on the Straits of Mackinac, written by a noted historian. In his account of the massacre, he says there was at this time no known surviving Ottawa Chief living on the south side of the Straits. This point of the history is incorrect, as there were several Ottawa chiefs living on the south side of the Straits at this particular time, who took no part in this massacre, but took by force the few survivors of this great, disastrous catastrophe, and protected them for a while and afterwards took them to Montreal, presenting them to the British Government; at the same time praying that their brother Odjebwes should not be retaliated upon on account of their rash act against the British people, but that they might be pardoned, as this terrible tragedy was committed through mistake, and through the evil counsel of one of their leaders by the name of Bwondiac (known in history as Pontiac). They told the British Government that their brother Odjebwes were few in number, while the British were in great numbers and daily increasing from an unknown part of the world across the ocean. They said, "Oh, my father, you are like the trees of the forest, and if one of the forest trees should be wounded with a hatchet, in a few years its wound will be entirely healed. Now, my father, compare with this: this is what my brother Odjebwe did to some of your children on the Straits of Mackinac, whose survivors we now bring back and present to your arms. O my father, have mercy upon my brothers and pardon them; for with your long arms and many, but a few strokes of retaliation would cause our brother to be entirely annihilated from the face of the earth!"

According to our understanding in our traditions, that was the time the British Government made such extraordinary promises to the Ottawa tribe of Indians, at the same time thanking them for their humane action upon those British remnants of the massacre. She promised them that her long arms will perpetually extend around them from generation to generation, or so long as there should be rolling sun. They should receive gifts from her sovereign in shape of goods, provisions, firearms, ammunition, and intoxicating liquors! Her sovereign's beneficent arm should be even extended unto the dogs belonging to the Ottawa tribe of Indians. And what place soever she should meet them, she would freely unfasten the faucet which contains her living water—whisky, which she will also cause to run perpetually and freely unto the Ottawas as the fountain of perpetual spring! And furthermore: she said, "I am as many as the stars in the heavens; and when you get up in the morning, look to the east; you will see that the sun, as it will peep through the earth, will be as red as my coat, to remind you why I am likened unto the sun, and my promises will be as perpetual as the rolling sun!"

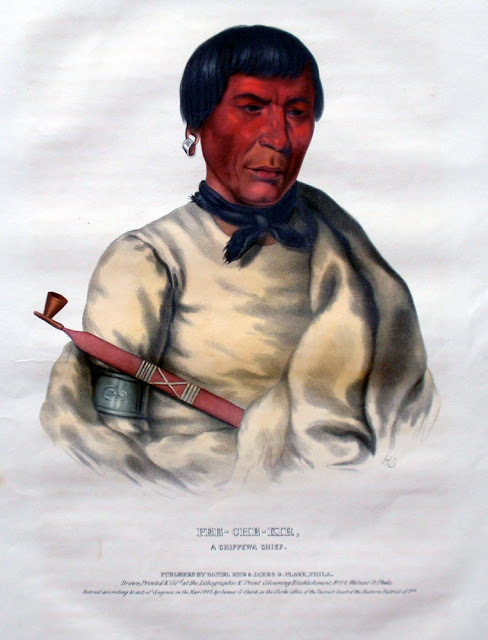

Ego-me-nay—Corn-hanger—was the head counselor and speaker of the Ottawa tribe of Indians at that time, and, according to our knowledge, Ego-me-nay was the leading one who went with those survivors of the massacre, and he was the man who made the speech before the august assembly in the British council hall at Montreal at that time. Ne-saw- key—Down-the-hill—the head chief of the Ottawa Nation, did not go with the party, but sent his message, and instructed their counselor in what manner he should appear before the British Government. My father was a little boy at that time, and my grandfather and my great- grandfather were both living then, and both held the first royal rank among the Ottawas. My grandfather was then a sub-chief and my great- grandfather was a war chief, whose name was Pun-go-wish: And several other chiefs of the tribe I could mention who existed at that time, but this is ample evidence that the historian was mistaken in asserting that there was no known Ottawa chief existing at the time of the massacre.

However it was a notable fact that by this time the Ottawas were greatly reduced in numbers from what they were in former times, on account of the small-pox which they brought from Montreal during the French war with Great Britain. This small pox was sold to them shut up in a tin box, with the strict injunction not to open the box on their way homeward, but only when they should reach their country; and that this box contained something that would do them great good, and their people! The foolish people believed really there was something in the box supernatural, that would do them great good. Accordingly, after they reached home they opened the box; but behold there was another tin box inside, smaller. They took it cut and opened the second box, and behold, still there was another box inside of the second box, smaller yet. So they kept on this way till they came to a very small box, which was not more than an inch long; and when they opened the last one they found nothing but mouldy particles in this last little box! They wondered very much what it was, and a great many closely inspected to try to find out what it meant. But alas, alas! pretty soon burst out a terrible sickness among them. The great Indian doctors themselves were taken sick and died. The tradition says it was indeed awful and terrible. Every one taken with it was sure to die. Lodge after lodge was totally vacated—nothing but the dead bodies lying here and there in their lodges—entire families being swept off with the ravages of this terrible disease. The whole coast of Arbor Croche, or Waw-gaw-naw- ke-zee, where their principal village was situated, on the west shore of the peninsula near the Straits, which is said to have been a continuous village some fifteen or sixteen miles long and extending from what is now called Cross Village to Seven-Mile Point (that is, seven miles from Little Traverse, now Harbor Springs), was entirely depopulated and laid waste. It is generally believed among the Indians of Arbor Croche that this wholesale murder of the Ottawas by this terrible disease sent by the British people, was actuated through hatred, and expressly to kill off the Ottawas and Chippewas because they were friends of the French Government or French King, whom they called "Their Great Father." The reason that to-day we see no full- grown trees standing along the coast of Arbor Croche, a mile or more in width along the shore, is because the trees were entirely cleared away for this famous long village, which existed before the small-pox raged among the Ottawas.

In my first recollection of the country of Arbor Croche, which is sixty years ago, there was nothing but small shrubbery here and there in small patches, such as wild cherry trees, but the most of it was grassy plain; and such an abundance of wild strawberries, raspberries and blackberries that they fairly perfumed the air of the whole coast with fragrant scent of ripe fruit. The wild pigeons and every variety of feathered songsters filled all the groves, warbling their songs joyfully and feasting upon these wild fruits of nature; and in these waters the fishes were so plentiful that as you lift up the anchor- stone of your net in the morning, your net would be so loaded with delicious whitefish as to fairly float with all its weight of the sinkers. As you look towards the course of your net, you see the fins of the fishes sticking out of the water in every way. Then I never knew my people to want for anything to eat or to wear, as we always had plenty of wild meat and plenty of fish, corn, vegetables, and wild fruits. I thought (and yet I may be mistaken) that my people were very happy in those days, at least I was as happy myself as a lark, or as the brown thrush that sat daily on the uppermost branches of the stubby growth of a basswood tree which stood near by upon the hill where we often played under its shade, lodging our little arrows among the thick branches of the tree and then shooting them down again for sport.

[Footnote: The word Arbor Croche is derived from two French words: Arbre, a tree; and Croche, something very crooked or hook-like. The tradition says when the Ottawas first came to that part of the country a great pine tree stood very near the shore where Middle Village now is, whose top was very crooked, almost hook-like. Therefore the Ottawas called the place "Waw-gaw-naw-ke-zee"—meaning the crooked top of the tree. But by and by the whole coast from Little Traverse to Tehin-gaw- beng, now Cross Village, became denominated as Waw-gaw-naw-ke-zee.]

Early in the morning as the sun peeped from the east, as I would yet be lying close to my mother's bosom, this brown thrush would begin his warbling songs perched upon the uppermost branches of the basswood tree that stood close to our lodge. I would then say to myself, as I listened to him, "here comes again my little orator," and I used to try to understand what he had to say; and sometimes thought I understood some of its utterances as follows: "Good morning, good morning! arise, arise! shoot, shoot! come along, come along!" etc., every word repeated twice. Even then, and so young as I was, I used to think that little bird had a language which God or the Great Spirit had given him, and every bird of the forest understood what he had to say, and that he was appointed to preach to other birds, to tell them to be happy, to be thankful for the blessings they enjoy among the summer green branches of the forest, and the plenty of wild fruits to eat. The larger boys used to amuse themselves by playing a ball called Paw-kaw-do-way, foot- racing, wrestling, bow-arrow shooting, and trying to beat one another shooting the greatest number of chipmunks and squirrels in a day, etc.

I never heard any boy or any grown person utter any bad language, even if they were out of patience with anything. Swearing or profanity was never heard among the Ottawa and Chippewa tribes of Indians, and not even found in their language. Scarcely any drunkenness, only once in a great while the old folks used to have a kind of short spree, particularly when there was any special occasion of a great feast going on. But all the young folks did not drink intoxicating liquors as a beverage in those days. And we always rested in perfect safety at night in our dwellings, and the doorways of our lodges had no fastenings to them, but simply a frail mat or a blanket was hung over our doorways which might be easily pushed or thrown one side without any noise if theft or any other mischief was intended. But we were not afraid for any such thing to happen us, because we knew that every child of the forest was observing and living under the precepts which their forefathers taught them, and the children were taught almost daily by their parents from infancy unto manhood and womanhood, or until they were separated from their families.

These precepts or moral commandments by which the Ottawa and Chippewa nations of Indians were governed in their primitive state, were almost the same as the ten commandments which the God Almighty himself delivered to Moses on Mount Sinai on tables of stone. Very few of these divine precepts are not found among the precepts of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, except with regard to the Sabbath day to keep it holy; almost every other commandment can be found, only there are more, as there were about twenty of these "uncivilized" precepts. They also believed, in their primitive state, that the eye of this Great Being is the sun by day, and by night the moon and stars, and, therefore, that God or the Great Spirit sees all things everywhere, night and day, and it would be impossible to hide our actions, either good or bad, from the eye of this Great Being. Even the very threshold or crevice of your wigwam will be a witness against you, if you should commit any criminal action when no human eye could observe your criminal doings, but surely your criminal actions will be revealed in some future time to your disgrace and shame. These were continual inculcations to the children by their parents, and in every feast and council, by the "Instructors of the Precepts" to the people or to the audience of the council. For these reasons the Ottawas and Chippewas in their primitive state were strictly honest and upright in their dealings with their fellow-beings. Their word of promise was as good as a promissory note, even better, as these notes sometimes are neglected and not performed according to their promises; but the Indian promise was very sure and punctual, although, as they had no timepieces, they measured their time by the sun. If an Indian promised to execute a certain obligation at such time, at so many days, and at such height of the sun, when that time comes he would be there punctually to fulfill this obligation. This was formerly the character of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan. But now, our living is altogether different, as we are continually suffering under great anxiety and perplexity, and continually being robbed and cheated in various ways. Our houses have been forcibly entered for thieving purposes and murder; people have been knocked down and robbed; great safes have been blown open with powder in our little town and their contents carried away, and even children of the Caucasian race are heard cursing and blaspheming the name of their Great Creator, upon whose pleasure we depended for our existence.

According to my recollection of the mode of living in our village, so soon as darkness came in the evening, the young boys and girls were not allowed to be out of their lodges. Every one of them must be called in to his own lodge for the rest of the night. And this rule of the Indians in their wild state was implicitly observed.

Ottawa and Chippewa Indians were not what we would call entirely infidels and idolaters; for they believed that there is a Supreme Ruler of the Universe, the Creator of all things, the Great Spirit, to which they offer worship and sacrifices in a certain form. It was customary among them, every spring of the year, to gather all the cast off garments that had been worn during the winter and rear them up on a long pole while they were having festivals and jubilees to the Great Spirit. The object of doing this was that the Great Spirit might look down from heaven and have compassion on his red children. Only this, that they foolishly believe that there are certain deities all over the lands who to a certain extent govern or preside over certain places, as a deity who presides over this river, over this lake, or this mountain, or island, or country, and they were careful not to express anything which might displease such deities; but that they were not supreme rulers, only to a certain extent they had power over the land where they presided. These deities were supposed to be governed by the Great Spirit above.