About Native American War

All Indians were more or less warlike; a few tribes, however, were eminent for their passion for war. Such, among eastern tribes, were the Iroquois; among southwestern tribes, the Apaches; and in Mexico, the Aztecs.

The purpose in Indian warfare was, everywhere, to inflict as much harm upon the enemy, and to receive as little as possible.

The causes of war were numerous—trespassing on tribal territory, stealing ponies, quarrels between individuals.

In their warfare stealthiness and craft were most important. Sometimes a single warrior crept silently to an unsuspecting camp that he might kill defenseless women, or little children, or sleeping warriors, and then as quietly he withdrew with his trophies.

Indian Spears, Shield, and Quiver of Arrows.

In such approaches, it was necessary to use every help in concealing oneself. Of the Apaches it is said: “He can conceal his swart body amidst the green grass, behind brown shrubs or gray rocks, with so much address and judgment that any one but the experienced would pass him by without detection at the distance of three or four yards. Sometimes they will envelop themselves in a gray blanket, and by an artistic sprinkling of earth will so resemble a granite bowlder as to be passed within near range without suspicion. At others, they will cover their person with freshly gathered grass, and lying prostrate, appear as a natural portion of the field. Again, they will plant themselves among the yuccas, and so closely imitate their appearance as to pass for one of them.”

At another time the Indian warrior would depend upon a sudden dash into the midst of the enemy, whereby he might work destruction and be away before his presence was fairly realized.

Clark tells of an unexpected assault made upon a camp by some white soldiers and Indian scouts. One of these scouts, named Three Bears, rode a horse that became unmanageable, and dashed with his rider into the very midst of the now angry and aroused enemy. Shots flew around him, and his life was in great peril. At that moment his friend, Feather-on-the-head, saw his danger. He dashed in after Three Bears. As he rode, he dodged back and forth, from side to side, in his saddle, to avoid shots. At the very center of the village, Three Bears' horse fell dead. Instantly, Feather-on-the-head, sweeping past, caught up his friend behind him on his own horse, and they were gone like a flash.

A favorite device in war was to draw the enemy into ambush. An attack would be made with a small part of the force. This would seem to make a brave assault, but would then fall back as if beaten. The enemy would press on in pursuit until some bit of woods, some little hollow, or some narrow place beneath a height was reached. Then suddenly the main body of attack, which had been carefully concealed, would rise to view on every side, and a massacre would ensue.

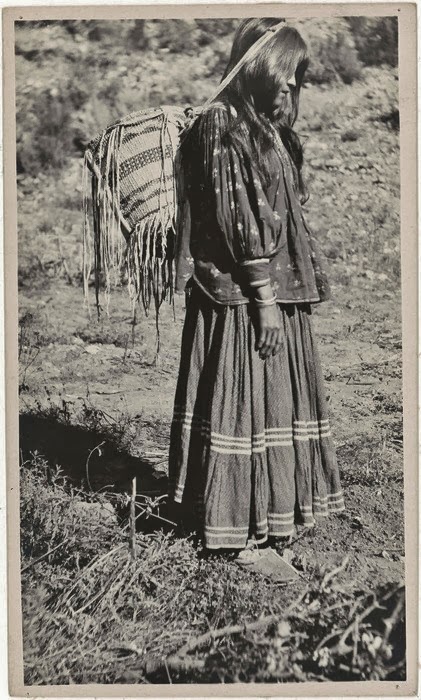

After the white man brought horses, the war expeditions were usually trips for stealing ponies. These, of course, were never common among eastern tribes; they were frequent among Plains Indians. Some man dreamed that he knew a village of hostile Indians where he could steal horses. If he were a brave and popular man, companions would promptly join him, on his announcing that he was going on an expedition. When the party was formed, the women prepared food, moccasins, and clothing. When ready, the party gathered in the medicine lodge, where they gashed themselves, took a sweat, and had prayers and charms repeated by the medicine man. Then they started. If they were to go far, at first they might travel night and day. As they neared their point of attack, they became more cautious, traveling only at night, and remaining concealed during the daylight. When they found a village or camp with horses, their care was redoubled. Waiting for night, they then approached rapidly but silently.

Each man worked by himself. Horses were quickly loosed and quietly driven away. When at a little distance from the village they gathered together, mounted the stolen animals, and fled. Once started, they pressed on as rapidly as possible.

It was the ambition of every Plains Indian to count coup. Coup is a French word, meaning a stroke or blow. It was considered an act of great bravery to go so near to a live enemy as to touch him with the hand, or to strike him with a short stick, or a little whip. As soon as an enemy had been shot and had fallen, three or four often would rush upon him, anxious to be the first one to touch him, and thus count coup.

There was really great danger in this, for a fallen enemy need not be badly injured, and may kill one who closely approaches him. More than this, when seriously injured and dying, a man in his last struggles is particularly dangerous. It was the ambition of every Indian youth to make coup for the first time, for thereafter he was considered brave, and greatly respected. Old men never tired of telling of the times they had made coup, and one who had thus touched dreaded enemies many times was looked upon as a mighty warrior.

Among certain tribes it was the custom to show the number of enemies killed by the wearing of war feathers. These were usually feathers of the eagle, and were cut or marked to show how many enemies had been slain. Among the Dakotas a war feather with a round spot of red upon it indicated one enemy slain; a notch in the edge showed that the throat of an enemy was cut; other peculiarities in the cut, trim, or coloration told other stories. Of course, such feathers were highly prized.

Every one has seen pictures of war bonnets made of eagle feathers. These consisted of a [crown or band, fitting the head, from which rose a circle of upright feathers; down the back hung a long streamer, a band of cloth sometimes reaching the ground, to which other feathers were attached so as to make a great crest. As many as sixty or seventy feathers might be used in such a bonnet, and, as one eagle only supplies a dozen, the bonnet represented the killing of five or six birds. These bonnets were often really worn in war, and were believed to protect the wearer from the missiles of the enemy.

The trophy prized above all others by American Indians was the scalp. Those made in later days by the Sioux consist of a small disk of skin from the head, with the attached hair. It was cut and torn from the head of wounded or dead enemies. It was carefully cleaned and stretched on a hoop; this was mounted on a stick for carrying. The skin was painted red on the inside, and the hair arranged naturally. If the dead man was a brave wearing war feathers, these were mounted on the hoop with the scalp.

It is said that the Sioux anciently took a much larger piece from the head, as the Pueblos always did. Among the latter, the whole haired skin, including the ears, was torn from the head. At Cochiti might be seen, until lately, ancient scalps with the ears, and in these there still remained the green turquoise ornaments.

Apache and Sioux Scalps.

While enemies were generally slain outright, such was not always the case. When prisoners, one of three other fates might await them: they might be adopted by some member of the tribe, in place of a dead brother or son; they might be made to run the gauntlet as a last and desperate chance of life. This was a severe test of agility, strength, and endurance. A man, given this chance, was obliged to run between two lines of Indians, all more or less armed, who struck at him as he passed. Usually the poor wretch fell, covered with wounds, long before he reached the end of the lines; if he passed through, however, his life was spared. Lastly, prisoners might be tortured to death, and dreadful accounts exist of such tortures among Iroquois, Algonkin and others. One of the least terrible was as follows: the unfortunate prisoner was bound to the stake, and the men and women picked open the flesh all over the body with knives; splinters of pine were then driven into the wounds and set on fire. The prisoner died in dreadful agony.