Free Archive of Historical documents and history of Native American tribes. Includes Indian Pictures, Photographs, and Images. Indian Pictures from the Iroquois Indians, Cheyenne Indians, Sioux Indians, Blackfoot Indians, Cherokee Indians Southwest Indians, California Native Americans and Algonquin Indians including complete history

Showing posts with label native american myths. Show all posts

Showing posts with label native american myths. Show all posts

Tuesday, April 22, 2014

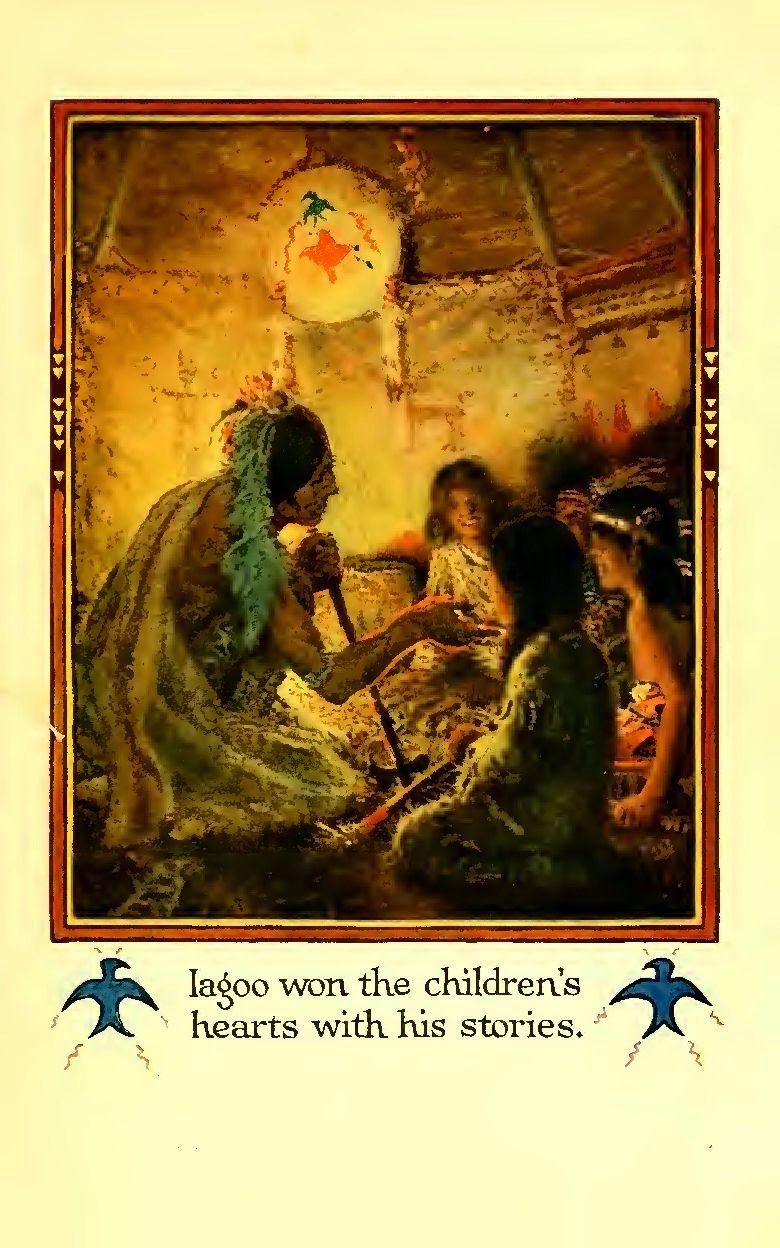

Native American Paintings Gallery

Native American, photos, gallery, pictures

artists,

gallery,

Native American,

native american myths,

paintings

Monday, May 14, 2012

The Mohegan Myths and Legends of the Flight of the Shawnee from the South

Native American Myths and Legends

THE FLIGHT OF THE SHAWNEES FROM

THE SOUTH.

A MOHEGAN TRADITION.

Metoxon states, that the Shawnees were, in ancient times, while they lived in the south, defeated by a confederacy of surrounding tribes, and in danger of being totally cut off and annihilated, had it not been for the interference of the Mohegans and Delawares. An alliance between them and the Mohegans, happened in this way. Whilst the Mohegans lived at Schodack, on the Hudson river, a young warrior of that tribe visited the Shawnees, at their southern residence, and formed a close friendship with a young warrior of his own age. They became as brothers, and vowed for ever to treat each other as such.

The Mohegan warrior had returned, and been some years living with his nation, on the banks of the Chatimac, or Hudson, when a general war broke out against the Shawnees. The restless and warlike disposition of this tribe, kept them constantly embroiled with their neighbours. They were unfaithful to their treaties, and this was the cause of perpetual troubles and wars. At length the nations of the south resolved, by a general effort, to rid themselves of so troublesome a people, and began a war, in which the Shawnees were defeated, battle after battle, with great loss. In this emergency, the Mohegan thought of his Shawnee brother, and resolved to rescue him. He raised a war-party and being joined by the Lenapees, since called Delawares, they marched to their relief, and brought off the remnant of the tribe to the country of the Lenapees. Here they were put under the charge of the latter, as their grandfather.

They were now, in the Indian phrase, put between their grandfather's knees, and treated as little children. Their hands were clasped and tied together—that is to say, they were taken under their protection, and formed a close alliance. But still, sometimes the child would creep out under the old man's legs, and get into trouble—implying that the Shawnees could never forget their warlike propensities.

The events of the subsequent history of this tribe, after the settlement of America are well known. With the Lenapees, or Delawares, they migrated westward.

The above tradition was received from the respectable and venerable chief, above named, in 1827, during the negotiation of the treaty of Buttes des Morts, on Fox river. At this treaty his people, bearing the modern name of Stockbridges, were present, having, within a few years, migrated from their former position in Oneida county, New York, to the waters of Fox river, in Wisconsin.

Metoxon was a man of veracity, and of reflective and temperate habits, united to urbanity of manners, and estimable qualities of head and heart, as I had occasion to know from several years' acquaintance with him, before he, and his people went from Vernon to the west, as well as after he migrated thither.

The tradition, perhaps with the natural partiality of a tribesman, lays too much stress upon a noble and generous act of individual and tribal friendship, but is not inconsistent with other relations, of the early southern position, and irrascible temper of the Shawnee tribe. Their name itself, which is a derivative from O-shá-wan-ong, the place of the South, is strong presumptive evidence of a former residence in, or origin from, the extreme south. Mr. John Johnston, who was for many years the government agent of this tribe at Piqua, in Ohio, traces them, in an article in the Archælogia Americana (vol. 1, p. 273) to the Suwanee river in Florida. Mr. Gallatin, in the second volume of the same work (p. 65) points out their track, from historical sources of undoubted authority, to the banks of the upper Savannah, in Georgia; but remarks that they have only been well known to us since 1680. They are first mentioned in our scattered Indian annals, by De Laet, in 1632.

It may further be said in relation to Metoxon's tradition, that there is authority for asserting, that in the flight of the Shawnees from the south, a part of them descended the Kentucky river west, to the Ohio valley, where, in after times, the Shawnees of Pennsylvania and New Jersey, rather formed a re-union with this division of their kindred than led the way for them.

To depart one step from barbarism, is to take one step towards civilization. To abandon the lodge of bark—to throw aside the blanket—to discontinue the use of paints—or to neglect the nocturnal orgies of the wabeno, are as certain indications of incipient civilization, as it unquestionably is, to substitute alphabetical characters for rude hieroglyphics, or to prefer the regular cadences of the gamut, to the wild chanting of the chichigwun.

Native American Myths and Legends: The Lynx and the Hare

THE LYNX AND THE HARE.

Native American Myths of the Lynx and the Hare

A FABLE FROM THE OJIBWA-ALGONQUIN.

A lynx almost famished, met a hare one day in the woods, in the winter season, but the hare was separated from its enemy by a rock, upon which it stood. The lynx began to speak to it in a very kind manner. "Wabose! Wabose!" said he, "come here my little white one, I wish to talk to you." "O no," said the hare, "I am afraid of you, and my mother told me never to go and talk with strangers." "You are very pretty," replied the lynx, "and a very obedient child to your parents; but you must know that I am a relative of yours; I wish to send some word to your lodge; come down and see me." The hare was pleased to be called pretty, and when she heard that it was a relative, she jumped down from the place where she stood, and immediately the lynx pounced upon her and tore her to pieces.

Monday, August 1, 2011

Native American Symbolism and Myths: The Bird and the Serpent

Relations of man to the lower animals.—Two of these, the Bird and the Serpent, chosen as symbols beyond all others.—The Bird throughout America the symbol of the Clouds and Winds.—Meaning of certain species.—The symbolic meaning of the Serpent derived from its mode of locomotion, its poisonous bite, and its power of charming.—Usually the symbol of the Lightning and the Waters.—The Rattlesnake the symbolic species in America.—The war charm.—The Cross of Palenque.—The god of riches.—Both symbols devoid of moral significance.

THOSE stories which the Germans call Thierfabeln, wherein the actors are different kinds of brutes, seem to have a particular relish for children and uncultivated nations. Who cannot recall with what delight he nourished his childish fancy on the pranks of Reynard the Fox, or the tragic adventures of Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf? Every nation has a congeries of such tales, and it is curious to mark how the same animal reappears with the same imputed physiognomy in all of them. The fox is always cunning, the wolf ravenous, the owl wise, and the ass foolish. The question has been raised whether such traits were at first actually ascribed to animals, or whether their introduction in story was intended merely as an agreeable figure of speech for classes of men. We cannot doubt but that the former was the case. Going back to the dawn of civilization, we find these relations not as amusing fictions, but as[100] myths, embodying religious tenets, and the brute heroes held up as the ancestors of mankind, even as rightful claimants of man’s prayers and praises.

Man, the paragon of animals, praying to the beast, is a spectacle so humiliating that, for the sake of our common humanity, we may seek the explanation of it least degrading to the dignity of our race. We must remember that as a hunter the primitive man was always matched against the wild creatures of the woods, so superior to him in their dumb certainty of instinct, their swift motion, their muscular force, their permanent and sufficient clothing. Their ways were guided by a wit beyond his divination, and they gained a living with little toil or trouble. They did not mind the darkness so terrible to him, but through the night called one to the other in a tongue whose meaning he could not fathom, but which, he doubted not, was as full of purport as his own. He did not recognize in himself those god-like qualities destined to endow him with the royalty of the world, while far more clearly than we do he saw the sly and strange faculties of his antagonists. They were to him, therefore, not inferiors, but equals—even superiors. He doubted not that once upon a time he had possessed their instinct, they his language, but that some necromantic spell had been flung on them both to keep them asunder. None but a potent sorcerer could break this charm, but such an one could understand the chants of birds and the howls of savage beasts, and on occasion transform himself into one or another animal, and course the forest, the air, or the waters, as he saw fit. Therefore, it was not the beast that he[101] worshipped, but that share of the omnipresent deity which he thought he perceived under its form.101-1

Beyond all others, two subdivisions of the animal kingdom have so riveted the attention of men by their unusual powers, and enter so frequently into the myths of every nation of the globe, that a right understanding of their symbolic value is an essential preliminary to the discussion of the divine legends. They are the Bird and the Serpent. We shall not go amiss if we seek the reasons of their pre-eminence in the facility with which their peculiarities offered sensuous images under which to convey the idea of divinity, ever present in the soul of man, ever striving at articulate expression.

The bird has the incomprehensible power of flight; it floats in the atmosphere, it rides on the winds, it soars toward heaven where dwell the gods; its plumage is stained with the hues of the rainbow and the sunset; its song was man’s first hint of music; it spurns the

clods

that impede his footsteps, and flies proudly over the mountains and moors where he toils wearily along. He sees no more enviable creature; he conceives the gods and angels must also have wings; and pleases himself with the fancy that he, too, some day will shake off this coil of clay, and rise on pinions to the heavenly mansions. All living beings, say the Eskimos, have the faculty of soul (tarrak), but especially the birds.101-2 As messengers from the upper world and interpreters of its[102] decrees, the flight and the note of birds have ever been anxiously observed as omens of grave import. “There is one bird especially,” remarks the traveller Coreal, of the natives of Brazil, “which they regard as of good augury. Its mournful chant is heard rather by night than day. The savages say it is sent by their deceased friends to bring them news from the other world, and to encourage them against their enemies.”102-1 In Peru and in Mexico there was a College of Augurs, corresponding in purpose to the auspices of ancient Rome, who practised no other means of divination than watching the course and professing to interpret the songs of fowls. So natural and so general is such a superstition, and so wide-spread is the respect it still obtains in civilized and Christian lands, that it is not worth while to summon witnesses to show that it prevailed universally among the red race also. What imprinted it with redoubled force on their imagination was the common belief that birds were not only divine nuncios, but the visible spirits of their departed friends. The Powhatans held that a certain small wood bird received the souls of their princes at death, and they refrained religiously from doing it harm;102-2 while the Aztecs and various other nations thought that all good people, as a reward of merit, were metamorphosed at the close of life into feathered songsters of the grove, and in this form passed a certain term in the umbrageous bowers of Paradise.

But the usual meaning of the bird as a symbol[103] looks to a different analogy—to that which appears in such familiar expressions as “the wings of the wind,” “the flying clouds.” Like the wind, the bird sweeps through the aerial spaces, sings in the forests, and rustles on its course; like the cloud, it floats in mid-air and casts its shadow on the earth; like the lightning, it darts from heaven to earth to strike its unsuspecting prey. These tropes were truths to savage nations, and led on by that law of language which forced them to conceive everything as animate or inanimate, itself the product of a deeper law of thought which urges us to ascribe life to whatever has motion, they found no animal so appropriate for their purpose here as the bird. Therefore the Algonkins say that birds always make the winds, that they create the water spouts, and that the clouds are the spreading and agitation of their wings;103-1 the Navajos, that at each cardinal point stands a white swan, who is the spirit of the blasts which blow from its dwelling; and the Dakotas, that in the west is the house of the Wakinyan, the Flyers, the breezes that send the storms. So, also, they frequently explain the thunder as the sound of the cloud-bird flapping his wings, and the lightning as the fire that flashes from his tracks, like the sparks which the buffalo scatters when he scours over a stony plain.103-2 The[104] thunder cloud was also a bird to the Caribs, and they imagined it produced the lightning in true Carib fashion by blowing it through a hollow reed, just as they to this day hurl their poisoned darts.104-1 Tupis, Iroquois, Athapascas, for certain, perhaps all the families of the red race, were the subject pursued, partook of this persuasion; among them all it would probably be found that the same figures of speech were used in comparing clouds and winds with the feathered species as among us, with however this most significant difference, that whereas among us they are figures and nothing more, to them they expressed literal facts.

How important a symbol did they thus become! For the winds, the clouds, producing the thunder and the changes that take place in the ever-shifting panorama of the sky, the rain bringers, lords of the seasons, and not this only, but the primary type of the soul, the life, the breath of man and the world, these in their role in mythology are second to nothing. Therefore as the symbol of these august powers, as messenger of the gods, and as the embodiment of departed spirits, no one will be surprised if they find the bird figure most prominently in the myths of the red race.

Sometimes some particular species seems to have been chosen as most befitting these dignified attributes. No citizen of the United States will be apt to assert that their instinct led the indigenes of our territory astray when they chose with nigh unanimous consent the great American eagle as that[105] fowl beyond all others proper to typify the supreme control and the most admirable qualities. Its feathers composed the war flag of the Creeks, and its images carved in wood or its stuffed skin surmounted their council lodges (Bartram); none but an approved warrior dare wear it among the Cherokees (Timberlake); and the Dakotas allowed such an honor only to him who had first touched the corpse of the common foe (De Smet). The Natchez and Akanzas seem to have paid it even religious honors, and to have installed it in their most sacred shrines (Sieur de Tonty, Du Pratz); and very clearly it was not so much for ornament as for a mark of dignity and a recognized sign of worth that its plumes were so highly prized. The natives of Zuñi, in New Mexico, employed four of its feathers to represent the four winds in their invocations for rain (Whipple), and probably it was the eagle which a tribe in Upper California (the Acagchemem) worshipped under the name Panes. Father Geronimo Boscana describes it as a species of vulture, and relates that one of them was immolated yearly, with solemn ceremony, in the temple of each village. Not a drop of blood was spilled, and the body burned. Yet with an amount of faith that staggered even the Romanist, the natives maintained and believed that it was the same individual bird they sacrificed each year; more than this, that the same bird was slain by each of the villages!105-1

The tender and hallowed associations that have so widely shielded the dove from harm, which for instance Xenophon mentions among the ancient Persians, were not altogether unknown to the tribes of the New World. Neither the Hurons nor Mandans would kill them, for they believed they were inhabited by the souls of the departed,

107-1 and it is said, but on less satisfactory authority, that they enjoyed similar immunity among the Mexicans. Their soft and plaintive note and sober russet hue widely enlisted the sympathy of man, and linked them with his more tender feelings.

“As wise as the serpent, as harmless as the dove,” is an antithesis that might pass current in any human language. They are the emblems of complementary, often contrasted qualities. Of all animals, the serpent is the most mysterious. No wonder it possessed the fancy of the observant child of nature. Alone of creatures it swiftly progresses without feet, fins, or wings. “There be three things which are too wonderful for me, yea, four which I know not,” said wise King Solomon; and the chief of them were, “the way of an eagle in the air, the way of a serpent upon a rock.”

Its sinuous course is like to nothing so much as that of a winding river, which therefore we often call serpentine. So did the Indians. Kennebec, a[108] stream in Maine, in the Algonkin means snake, and Antietam, the creek in Maryland of tragic celebrity, in an Iroquois dialect has the same significance. How easily would savages, construing the figure literally, make the serpent a river or water god! Many species being amphibious would confirm the idea. A lake watered by innumerable tortuous rills wriggling into it, is well calculated for the fabled abode of the king of the snakes. Thus doubtless it happened that both Algonkins and Iroquois had a myth that in the great lakes dwelt a monster serpent, of irascible temper, who unless appeased by meet offerings raised a tempest or broke the ice beneath the feet of those venturing on his domain, and swallowed them down.108-1

In snake charming as a proof of proficiency in magic, and in the symbol of the lightning, which brings both fire and water, which in its might controls victory in war, and in its frequency, plenteous crops at home, lies the secret of the serpent symbol. As the “war physic” among the tribes of the United States was a fragment of a serpent, and as thus signifying his incomparable skill in war, the Iroquois[118] represent their mythical king Atatarho clothed in nothing but black snakes; so that when he wished to don a new suit he simply drove away one set and ordered another to take their places,118-1 so, by a precisely similar mental process, the myth of the Nahuas assigns as a mother to their war god Huitzilapochtli, Coatlicue, the robe of serpents; her dwelling place Coatepec, the hill of serpents; and at her lying-in say that she brought forth a serpent. Her son’s image was surrounded by serpents, his sceptre was in the shape of one, his great drum was of serpents’ skins, and his statue rested on four vermiform caryatides.

As the symbol of the fertilizing summer showers the lightning serpent was the god of fruitfulness. Born in the atmospheric waters, it was an appropriate attribute of the ruler of the winds. But we have already seen that the winds were often spoken of as great birds. Hence the union of these two emblems in such names as Quetzalcoatl, Gucumatz, Kukulkan, all titles of the god of the air in the languages of Central America, all signifying the “Bird-serpent.” Here also we see the solution of that monument which has so puzzled American antiquaries, the cross at Palenque. It is a tablet on the wall of an altar representing a cross surmounted by a bird and supported by the head of a serpent. The latter is not well defined in the plate in Mr. Stephens’ Travels, but is very distinct in the photographs taken by M. Charnay, which that gentleman was kind enough to show me. The cross I have previously shown was the symbol of the four winds, and the bird and serpent[119] are simply the rebus of the air god, their ruler.119-1 Quetzalcoatl, called also Yolcuat, the rattlesnake, was no less intimately associated with serpents than with birds. The entrance to his temple at Mexico represented the jaws of one of these reptiles, and he finally disappeared in the province of Coatzacoalco, the hiding place of the serpent, sailing towards the east in a bark of serpents’ skins. All this refers to his power over the lightning serpent.

He was also said to be the god of riches and the patron consequently of merchants. For with the summer lightning come the harvest and the ripening fruits, come riches and traffic. Moreover “the golden color of the liquid fire,” as Lucretius expresses it, naturally led where this metal was known, to its being deemed the product of the lightning. Thus originated many of those tales of a dragon who watches a treasure in the earth, and of a serpent who is the dispenser of riches, such as were found among the Greeks and ancientGermans.119-2 So it was in Peru where the god of riches was worshipped under the image of a rattlesnake horned and hairy, with a tail of gold. It was said to have descended from the heavens in the sight of all the people, and to have been seen by the whole army of the Inca.119-3 Whether[120] it was in reference to it, or as emblems of their prowess, that the Incas themselves chose as their arms two serpents with their tails interlaced, is uncertain; possibly one for each of these significations.

Because the rattlesnake, the lightning serpent, is thus connected with the food of man, and itself seems never to die but annually to renew its youth, the Algonkins called it “grandfather” and “king of snakes;” they feared to injure it; they believed it could grant prosperous breezes, or raise disastrous tempests; crowned with the lunar crescent it was the constant symbol of life in their picture writing; and in the meda signs the mythical grandmother of mankind me suk kum me go kwa was indifferently represented by an old woman or a serpent.120-1 For like reasons Cihuacoatl, the Serpent Woman, in the myths of the Nahuas was also called Tonantzin, our mother.120-2

The serpent symbol in America has, however, been brought into undue prominence. It had such an ominous significance in Christian art, and one which chimed so well with the favorite proverb of the early missionaries—“the gods of the heathens are devils”—that wherever they saw a carving or picture of a serpent they at once recognized the sign manual of the Prince of Darkness, and inscribed the fact in their note-books as proof positive of their cherished theory.[121] After going over the whole ground, I am convinced that none of the tribes of the red race attached to this symbol any ethical significance whatever, and that as employed to express atmospheric phenomena, and the recognition of divinity in natural occurrences, it far more frequently typified what was favorable and agreeable than the reverse.

Native American's Wampum Massacre on the Wabash, the Miami Indians Defeat of St. Clair

Native American, photos, gallery, pictures

native american myths,

native american symbol,

native american symbols,

native american symbols and meanings,

native american symbols meanings

Native American Numerology of the Number Four

Native American Numerology of the Number Four

The Tarleton Cross, constructed by the Hopewell Sioux is one of many earthworks that revolve around the number 4. This earthwork is aligned to the cardinal points.

EVERY one familiar with the ancient religions of the world must have noticed the mystic power they attach to certain numbers, and how these numbers became the measures and formative quantities, as it were, of traditions and ceremonies, and had a symbolical meaning nowise connected with their arithmetical value. For instance, in many eastern religions, that of the Jews among the rest, seven was the most sacred number, and after it, four and three. The most cursory reader must have observed in how many connections the seven is used in the Hebrew Scriptures, occurring, in all, something over three hundred and sixty times, it is said. Why these numbers were chosen rather than others has not been clearly explained. Their sacred character dates beyond the earliest history, and must have been coeval with the first expressions of the religious sentiment. Only one of them, the FOUR, has any prominence in[67] the religions of the red race, but this is so marked and so universal, that at a very early period in my studies I felt convinced that if the reason for its adoption could be discovered, much of the apparent confusion which reigns among them would be dispelled.

Such a reason must take its rise from some essential relation of man to nature, everywhere prominent, everywhere the same. It is found in the adoration of the cardinal points.

The assumption of precisely four cardinal points is not of chance; it is recognized in every language; it is rendered essential by the anatomical structure of the body; it is derived from the immutable laws of the universe. Whether we gaze at the sunset or the sunrise, or whether at night we look for guidance to the only star of the twinkling thousands that is constant to its place, the anterior and posterior planes of our bodies, our right hands and our left coincide with the parallels and meridians. Very early in his history did man take note of these four points, and recognizing in them his guides through the night and

[68] the wilderness, call them his gods. Long afterwards, when centuries of slow progress had taught him other secrets of nature—when he had discerned in the motions of the sun, the elements of matter, and the radicals of arithmetic a repetition of this number—they were to him further warrants of its sacredness. He adopted it as a regulating quantity in his institutions and his arts; he repeated it in its multiples and compounds; he imagined for it novel applications; he constantly magnified its mystic meaning; and finally, in his philosophical reveries, he called it the key to the secrets of the universe, “the source of ever-flowing nature.”68-1

Proximity of place had no part in this similarity of rite. In the grand commemorative festival of the Creeks called the Busk, which wiped out the memory of all crimes but murder, which reconciled the proscribed criminal to his nation and atoned for his guilt, when the new fire was kindled and the green corn served up, every dance, every invocation, every ceremony, was shaped and ruled by the application of the

[ number four and its multiples in every imaginable relation. So it was at that solemn probation which the youth must undergo to prove himself worthy of the dignities of manhood and to ascertain his guardian spirit; here again his fasts, his seclusions, his trials, were all laid down in four fold arrangement.

Not alone among these barbarous tribes were the cardinal points thus the foundation of the most solemn mysteries of religion. An excellent authority relates that the Aztecs of Micla, in Guatemala, celebrated their chief festival four times a year, and that four priests solemnized its rites. They commenced by invoking and offering incense to the sky and the four cardinal points; they conducted the human victim four times around the temple, then tore out his heart, and catching the blood in four vases scattered it in the samedirections.72-2 So also the Peruvians had four principal festivals annually, and at every new moon one of four days’ duration. In fact the repetition of the number in all their religious ceremonies is so prominent that it has been a subject of comment by historians. They have attributed it to the knowledge of the solstices and equinoxes, but assuredly it is of more ancient date than this. The same explanation has been offered for its recurrence among the Nahuas of Mexico, whose whole lives[73] were subjected to its operation. At birth the mother was held unclean for four days, a fire was kindled and kept burning for a like length of time, at the baptism of the child an arrow was shot to each of the cardinal points. Their prayers were offered four times a day, the greatest festivals were every fourth year, and their offerings of blood were to the four points of the compass. At death food was placed on the grave, as among the Eskimos, Creeks, and Algonkins, for four days (for all these nations supposed that the journey to the land of souls was accomplished in that time), and mourning for the dead was for four months or four years.

It were fatiguing and unnecessary to extend the catalogue much further. Yet it is not nearly exhausted. From tribes of both continents and all stages of culture, the Muyscas of Columbia and the Natchez of Louisiana, the Quichés of Guatemala and the Caribs of the Orinoko, instance after instance might be marshalled to illustrate how universally a sacred character was attached to this number, and how uniformly it is traceable to a veneration of the cardinal points. It is sufficient that it be displayed in some of its more unusual applications.

It is well known that the calendar common to the] Aztecs and Mayas divides the month into four weeks, each containing a like number of secular days; that their indiction is divided into four periods; and that they believed the world had passed through four cycles. It has not been sufficiently emphasized that in many of the picture writings these days of the week are placed respectively north, south, east, and west, and that in the Maya language the quarters of the indiction still bear the names of the cardinal points, hinting the reason of their adoption.74-1 This cannot be fortuitous. Again, the division of the year into four seasons—a division as devoid of foundation in nature as that of the ancient Aryans into three, and unknown among many tribes, yet obtained in very early times among Algonkins, Cherokees, Choctaws, Creeks, Aztecs, Muyscas, Peruvians, and Araucanians. They were supposed to be produced by the unending struggles and varying fortunes of the four aerial giants who rule the winds.

We must seek in mythology the key to the monotonous repetition and the sanctity of this number; and furthermore, we must seek it in those natural modes of expression of the religious sentiment which are above the power of blood or circumstance to control. One of these modes, we have seen, was that which led to the identification of the divinity with the wind, and this it is that solves the enigma in the present instance. Universally the spirits of the cardinal points were imagined to be in the winds that blew from them. The names of these directions and[75] of the corresponding winds are often the same, and when not, there exists an intimate connection between them. For example, take the languages of the Mayas, Huastecas, and Moscos of Central America; in all of them the word for north is synonymous with north wind, and so on for the other three points of the compass. Or again, that of the Dakotas, and the word tate-ouye-toba, translated “the four quarters of the heavens,” means literally, “whence the four winds come.”75-1 It were not difficult to extend the list; but illustrations are all that is required. Let it be remembered how closely the motions of the air are associated in thought and language with the operations of the soul and the idea of God; let it further be considered what support this association receives from the power of the winds on the weather, bringing as they do the lightning and the storm, the zephyr that cools the brow, and the tornado that levels the forest; how they summon the rain to fertilize the seed and refresh the shrivelled leaves; how they aid the hunter to stalk the game, and usher in the varying seasons; how, indeed, in a hundred ways, they intimately concern his comfort and his life; and it will not seem strange that they almost occupied the place of all other gods in the mind of the child of nature. Especially as those who gave or withheld the rains were they objects of his anxious solicitation. “Ye who dwell at the four corners of the earth—at the north, at the south, at the east, and at the west,” commenced the Aztec prayer to the Tlalocs, gods of the showers.75-2 [76]For they, as it were, hold the food, the life of man in their power, garnered up on high, to grant or deny, as they see fit. It was from them that the prophet of old was directed to call back the spirits of the dead to the dry bones of the valley. “Prophesy unto the wind, prophesy, son of man, and say to the wind, thus saith the Lord God, come forth from the four winds, O breath, and breathe upon these slain, that they may live.” (Ezek. xxxvii. 9.)

In the same spirit the priests of the Eskimos prayed to Sillam Innua, the Owner of the Winds, as the highest existence; the abode of the dead they called Sillam Aipane, the House of the Winds; and in their incantations, when they would summon a new soul to the sick, or order back to its home some troublesome spirit, their invocations were ever addressed to the winds from the cardinal points—to Pauna the East and Sauna the West, to Kauna the South and Auna the North.

As the rain-bringers, as the life-givers, it were no far-fetched metaphor to call them the fathers of our race. Hardly a nation on the continent but seems to have had some vague tradition of an origin from four brothers, to have at some time been led by four leaders or princes, or in some manner to have connected the appearance and action of four important personages with its earliest traditional history. Sometimes the myth defines clearly these fabled characters as the spirits of the winds, sometimes it clothes them in uncouth, grotesque metaphors, sometimes again it s weaves them into actual history that we are at a loss where to draw the line that divides fiction from truth.

I shall attempt to follow step by step the growth of this myth from its simplest expression, where the transparent drapery makes no pretence to conceal its true meaning, through the ever more elaborate narratives, the more strongly marked personifications of more cultivated nations, until it assumes the outlines of, and has palmed itself upon the world as actual history.

This simplest form is that which alone appears among the Algonkins and Dakotas. They both traced their lives back to four ancestors, personages concerned in various ways with the first things of time, not rightly distinguished as men or gods, but very positively identified with the four winds. Whether from one or all of these the world was peopled, whether by process of generation or some other more obscure way, the old people had not said, or saying, had not agreed.

It is a shade more complex when we come to the Creeks. They told of four men who came from the four corners of the earth, who brought them the sacred fire, and pointed out the seven sacred plants. They were called the Hi-you-yul-gee. Having rendered them this service, the kindly visitors disappeared in a cloud, returning whence they came. When another and more ancient legend informs us that the Creeks were at first divided into four clans, and alleged a descent from four female ancestors, it[78] will hardly be venturing too far to recognize in these four ancestors the four friendly patrons from the cardinal points.

The Navajos are a rude tribe north of Mexico. Yet even they have an allegory to the effect that when the first man came up from the ground under the figure of the moth-worm, the four spirits of the cardinal points were already there, and hailed him with the exclamation, “Lo, he is of our race.”

Wherever, in short, the lust of gold lured the early adventurers, they were told of some nation a little further on, some wealthy and prosperous land, abundant and fertile, satisfying the desire of the heart. It was sometimes deceit, and it was sometimes the credited fiction of the earthly paradise, that in all ages has with a promise of perfect joy consoled the aching heart of man.

It is instructive to study the associations that naturally group themselves around each of the cardinal points, and watch how these are mirrored on the surface of language, and have directed the current of[] thought. Jacob Grimm has performed this task with fidelity and beauty as regards the Aryan race, but the means are wanting to apply his searching method to the indigenous tongues of America. Enough if in general terms their mythological value be determined.

When the day begins, man wakes from his slumbers, faces the rising sun, and prays. The east is before him; by it he learns all other directions; it is to him what the north is to the needle; with reference to it he assigns in his mind the position of the three other cardinal points. There is the starting place of the celestial fires, the home of the sun, the womb of the morning. It represents in space the beginning of things in time, and as the bright and glorious creatures of the sky come forth thence, man conceits that his ancestors also in remote ages wandered from the orient; there in the opinion of many in both the old and new world was the cradle of the race; there in Aztec legend was the fabled land of Tlapallan, and the wind from the east was called the wind of Paradise, Tlalocavitl.

From this direction came, according to the almost unanimous opinion of the Indian tribes, those hero gods who taught them arts and religion, thither they returned, and from thence they would again appear to resume their ancient sway. As the dawn brings light, and with light is associated in every human mind the ideas of knowledge, safety, protection, majesty, divinity, as it dispels the spectres of night, as it

defines the cardinal points, and brings forth the sun and the day, it occupied the primitive mind to an extent that can hardly be magnified beyond the truth. It is in fact the central figure in most natural religions.

The west, as the grave of the heavenly luminaries, or rather as their goal and place of repose, brings with it thoughts of sleep, of death, of tranquillity, of rest from labor. When the evening of his days was come, when his course was run, and man had sunk from sight, he was supposed to follow the sun and find some spot of repose for his tired soul in the distant west. There, with general consent, the tribes north of the Gulf of Mexico supposed the happy hunting grounds; there, taught by the same analogy, the ancient Aryans placed the Nerriti, the exodus, the land of the dead. “The old notion among us,” said on one occasion a distinguished chief of the Creek nation, “is that when we die, the spirit goes the way the sun goes, to the west, and there joins its family and friends who went before it.”

In the northern hemisphere the shadows fall to the north, thence blow cold and furious winds, thence come the snow and early thunder. Perhaps all its primitive inhabitants, of whatever race, thought it the seat of the mighty gods. A floe of ice in the Arctic Sea was the home of the guardian spirit of the Algonkins;92-3 on a mountain near the north star the Dakotas thought Heyoka dwelt who rules the seasons; and the realm of Mictla, the Aztec god of death, lay where the shadows pointed. From that cheerless[ abode his sceptre reached over all creatures, even the gods themselves, for sooner or later all must fall before him. The great spirit of the dead, said the Ottawas, lives in the dark north,93-1 and there, in the opinion of the Monquis of California, resided their chief god, Gumongo.93-2

Unfortunately the makers of vocabularies have rarely included the words north, south, east, and west, in their lists, and the methods of expressing these ideas adopted by the Indians can only be partially discovered. The east and west were usually called from the rising and setting of the sun as in our words orient and occident, but occasionally from traditional notions. The Mayas named the west the greater, the east the lesser debarkation; believing that while their culture hero Zamna came from the east with a few attendants, the mass of the population arrived from the opposite direction.93-3 The Aztecs spoke of the east as “the direction of Tlalocan,” the terrestrial paradise. But for north and south there were no such natural appellations, and consequently the greatest diversity is exhibited in the plans adopted to express them. The north in the Caddo tongue is “the place of cold,” in Dakota “the situation of the pines,” in Creek “the abode of the (north) star,” in Algonkin “the home of the soul,” in Aztec “the direction of Mictla” the realm of death, in Quiché and Quichua, “to the right hand;”93-4 while for] the south we find such terms as in Dakota “the downward direction,” in Algonkin “the place of warmth,” in Quiché “to the left hand,” while among the Eskimos, who look in this direction for the sun, its name implies “before one,” just as does the Hebrew word kedem, which, however, this more southern tribe applied to the east.

We can trace the sacredness of the number four in other curious and unlooked-for developments. Multiplied into the number of the fingers—the arithmetic of every child and ignorant man—or by adding together the first four members of its arithmetical series (4 + 8 + 12 + 16), it gives the number forty. This was taken as a limit to the sacred dances of some Indian tribes, and by others as the highest number of chants to be employed in exorcising diseases. Consequently it came to be fixed as a limit in exercises of preparation or purification. The females of the Orinoko tribes fasted forty days before marriage, and those of the upper Mississippi were held unclean the same length of time after childbirth; such was the term of the Prince of Tezcuco’s fast when he wished an heir to his throne, and such the number of days the Mandans supposed it required to wash clean the world at thedeluge.94-1

[95]No one is ignorant how widely this belief was prevalent in the old world, nor how the quadrigesimal is still a sacred term with some denominations of Christianity. But a more striking parallelism awaits us. The symbol that beyond all others has fascinated the human mind, THE CROSS, finds here its source and meaning. Scholars have pointed out its sacredness in many natural religions, and have reverently accepted it as a mystery, or offered scores of conflicting and often debasing interpretations. It is but another symbol of the four cardinal points, the four winds of heaven. This will luminously appear by a study of its use and meaning in America.

When the rain maker of the Lenni Lenape would exert his power, he retired to some secluded spot and drew upon the earth the figure of a cross (its arms toward the cardinal points?), placed upon it a piece of tobacco, a gourd, a bit of some red stuff, and commenced to cry aloud to the spirits of the rains.

96-3 The Creeks at the festival of the Busk, celebrated, as we have seen, to the four winds, and according to their legends instituted by them, commenced with making[97] the new fire. The manner of this was “to place four logs in the centre of the square, end to end, forming a cross, the outer ends pointing to the cardinal points; in the centre of the cross the new fire is made.”97-1

As the emblem of the winds who dispense the fertilizing showers it is emphatically the tree of our life, our subsistence, and our health. It never had any other meaning in America, and if, as has been said,97-2 the tombs of the Mexicans were cruciform, it was perhaps with reference to a resurrection and a future life as portrayed under this symbol, indicating that the buried body would rise by the action of the four spirits of the world, as the buried seed takes on a new existence when watered by the vernal showers. It frequently recurs in the ancient Egyptian writings, where it is interpreted life; doubtless, could we trace the hieroglyph to its source, it would likewise prove to be derived from the four winds.

While thus recognizing the natural origin of this consecrated symbol, while discovering that it is based on the sacredness of numbers, and this in turn on[98] the structure and necessary relations of the human body, thus disowning the meaningless mysticism that Joseph de Maistre and his disciples have advocated, let us on the other hand be equally on our guard against accepting the material facts which underlie these beliefs as their deepest foundation and their exhaustive explanation. That were but withered fruit for our labors, and it might well be asked, where is here the divine idea said to be dimly prefigured in mythology? The universal belief in the sacredness of numbers is an instinctive faith in an immortal truth; it is a direct perception of the soul, akin to that which recognizes a God. The laws of chemical combination, of the various modes of motion, of all organic growth, show that simple numerical relations govern all the properties and are inherent to the very constitution of matter; more marvellous still, the most recent and severe inductions of physicists show that precisely those two numbers on whose symbolical value much of the edifice of ancient mythology was erected, the four and the three, regulate the molecular distribution of matter and preside over the symmetrical development of organic forms. This asks no faith, but only knowledge; it is science, not revelation. In view of such facts is it presumptuous to predict that experiment itself will prove the truth of Kepler’s beautiful saying: “The universe is a harmonious whole, the soul of which is God; numbers, figures, the stars, all nature, indeed, are in unison with the mysteries of religion”?

Native American's Wampum Massacre on the Wabash, the Miami Indians Defeat of St. Clair

Native American's Wampum Massacre on the Wabash, the Miami Indians Defeat of St. Clair

Native American, photos, gallery, pictures

native american beliefs,

native american myths,

Ohio,

Sacred numbers,

Tarleton Cross

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)