Dakota Sioux Platform Burials and Mourning Ceremony

Before the year 1860 it was a custom, for as long back as the oldest members of these tribes can remember, and with the usual tribal traditions handed down from generation to generation, in regard to this as well as to other things, for these Indians to bury in a tree or on a platform, and in those days an Indian was only buried in the ground as a mark of disrespect in consequence of the person having been murdered, in which case the body would be buried in the ground,

face down, head toward the south and with a piece of fat in the mouth.

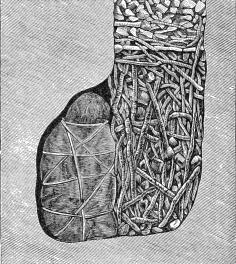

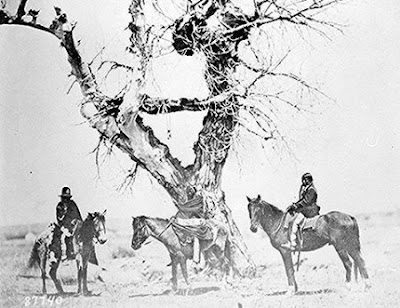

*** The platform upon which the body was deposited was constructed of four

crotched posts firmly set in the ground, and connected near the top by

cross-pieces, upon which was placed boards, when obtainable, and small sticks of wood, sometimes hewn so as to give a firm resting-place

for the body. This platform had an elevation of from six to eight or more feet, and never contained but one body, although frequently having

sufficient surface to accommodate two or three. In burying in the crotch of a tree and on platforms, the head of the dead person was always placed towards the south; the body was wrapped in blankets or pieces of cloth securely tied, and many of the personal effects

109of the deceased were buried with it; as in the case of a warrior, his bows and arrows, war-clubs, &c., would be placed alongside of the body, the Indians

saying he would need such things in the next world.

I am informed by many of them that it was a habit, before their outbreak, for some to carry the body of a near relative whom they held in great respect with them on their moves, for a greater or lesser time, often as long as two or three years before burial. This, however, never obtained generally among them, and some of them seem to know nothing about it. It has of late years been entirely dropped, except when a person dies away from home, it being then customary for the friends to bring the body home for burial.

Mourning ceremonies.—The mourning ceremonies before the year 1860 were as follows: After the death of a warrior the whole camp or tribe would be assembled in a circle, and after the widow had cut herself on the arms, legs, and body with a piece of flint, and removed the hair from her head, she would go around the ring any number of times she chose, but each time was considered as an oath that she would not marry for a year, so that she could not marry for as many years as times she went around the circle. The widow would all this time keep up a crying and wailing. Upon the completion of this the friends of the deceased would take the body to the platform or tree where it was to remain, keeping up all this time their wailing and crying. After depositing the body, they would stand under it and continue exhibiting their grief, the squaws by hacking their arms and legs with flint and cutting off the hair from their head. The men would sharpen sticks and run them through the skin of their arms and legs, both men and women keeping up their crying generally for the remainder of the day, and the near relatives of the deceased for several days thereafter. As soon as able, the warrior friends of the deceased would go to a near tribe of their enemies and kill one or more of them if possible, return with their scalps, and exhibit them to the deceased person’s relatives, after which their mourning ceased, their friends considering his death as properly avenged; this, however, was many years ago, when their enemies were within reasonable striking distance, such, for instance, as the Chippewas and the Arickarees, Gros Ventres and Mandan Indians. In cases of women and children, the squaws would cut off their hair, hack their persons with flint, and sharpen sticks and run them through the skin of the arms and legs, crying as for a warrior.

It was an occasional occurrence twenty or more years ago for a squaw when she lost a favorite child to commit suicide by hanging herself with a lariat over the limb of a tree. This could not have prevailed to any great extent, however, although the old men recite several instances of its occurrence, and a very few examples within recent years. Such was their custom before the Minnesota outbreak, since which time it has gradually died out, and at the present time these ancient customs are adhered to by but a single family, known as the seven brothers, who appear to retain all the ancient customs of their tribe. At the present time, as a mourning observance, the squaws hack themselves on their legs with knives, cut off their hair, and cry and wail around the grave of the dead person, and the men in addition paint their faces, but no longer torture themselves by means of sticks passed through the skin of the arms and legs. This cutting and painting

is sometimes done before and sometimes after the burial of the body. I also observe that many of the women of these tribes are adopting so

much of the customs of the whites as prescribes the wearing of black for certain periods. During the period of mourning these Indians never wash their face, or comb their hair, or laugh. These customs are observed with varying degree of strictness, but not in many instances with that exactness which characterized these Indians before the advent of the white man among them. There is not now any permanent mutilation of the person practiced as a mourning ceremony by them. That mutilation of a finger by removing one or more joints, so generally observed among the Minnetarree Indians at the Fort Berthold, Dak., Agency, is not here seen, although the old men of these tribes inform me that it was an ancient custom among

110their women, on the occasion of the burial of a husband, to cut off a portion of a finger and have it suspended in the tree above his body. I have, however, yet to see an example of this having been done by any of the Indians now living, and the custom must have fallen into disuse more than seventy years ago.

In regard to the period of mourning, I would say that there does not now appear to be, and, so far as I can learn, never was, any fixed period of mourning, but it would seem that, like some of the whites, they mourn when the subject is brought to their minds by some remark or other occurrence. It is not unusual at the present time to hear a man or woman cry and exclaim, “O, my poor husband!” “O, my poor wife!” or “O, my poor child!” as the case may be, and, upon inquiring, learn that the event happened several years before. I have elsewhere mentioned that in some cases much of the personal property of the deceased was and is reserved from burial with the body, and forms the basis of a gambling party. I shall conclude my remarks upon the burial customs, &c., of these Indians by an account of this, which they designate as the “ghost’s gamble.”