The Dakota Sioux Spirit World

The Dakotas believe in the existence of a Great Spirit, but they have very confused ideas of his attributes. Those who have lived near the missionaries, say that the Great Spirit lived forever, but their own minds would never have conceived such an idea. Some say that the Great Spirit has a wife.

They say that this being created all things but thunder and wild rice; and that he gave the earth and all animals to them, and that their feasts and customs were the laws by which they are to be governed. But they do not fear the anger of this deity after death.

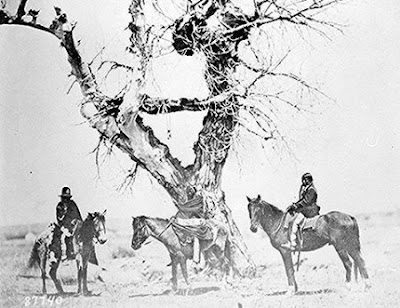

Native American Religions Depicted on Photos HereThunder is said to be a large bird; the name that they give to thunder is the generic term for all animals that fly. Near the source of the St. Peters is a place called Thunder-tracks—where the footprints of the thunder-bird are seen in the rocks, twenty-five miles apart.

The Dakotas believe in an evil spirit as well as a good, but they do not consider these spirits as opposed to each other; they do not think that they are tempted to do wrong by this evil spirit; their own hearts are bad. It would be impossible to put any limit to the number of spirits in whom the Dakotas believe; every object in nature is full of them. They attribute death as much to the power of these subordinate spirits as to the Great Spirit; but most frequently they suppose death to have been occasioned by a spell having been cast upon them by some enemy.

Photos and images of the Dakota IndiansThe sun and moon are worshipped as emblems of their deity.

Sacrifice is a religious ceremony among them; but no missionary has yet been able to find any reference to the one great Atonement made for sin; none of their customs or traditions authorize any such connection. They sacrifice to all the spirits; but they have a stone, painted red, which they call Grandfather, and on or near this, they place their most valuable articles, their buffalo robes, dogs, and even horses; and on one occasion a father killed a child as a kind of sacrifice. They frequently inflict severe bruises or cuts upon their bodies, thinking thus to propitiate their gods.

The belief in an evil spirit is said by some not to be a part of the religion of the Dakota. They perhaps obtained this idea from the whites. They have a far greater fear of the spirits of the dead, especially those whom they have offended, than of Wahkon-tun-kah, the Great Spirit.

* * * * *

One of the punishments they most dread is that of the body of an animal entering theirs to make them sick. Some of the medicine men, the priests, and the doctors of the Dakota, seem to have an idea of the immortality of the soul but intercourse with the whites may have originated this. They know nothing of the resurrection.

They have no custom among them that indicates the belief that man's heart should be holy. The faith in spirits, dreams, and charms, the fear that some enemy, earthly or spiritual, may be secretly working their destruction by a spell, is as much a part of their creed, as the existence of the Great Spirit.

A good dream will raise their hopes of success in whatever they may be undertaking to the highest pitch; a bad one will make them despair of accomplishing it. Their religion is a superstition, including as few elements of truth and reason as perhaps any other of which the particulars are known. They worship they "know not what," and this from the lowest motives.

When they go out to hunt, or on a war party, they pray to the Great Spirit—"Father, help us to kill the buffalo." "Let us soon see deer"—or, "Great Spirit help us to kill our enemies."

They have no hymns of praise to their Deity; they fast occasionally at the time of their dances. When they dance in honor of the sun, they refrain from eating for two days.

The Dakotas do not worship the work of their hands; but they consider every object that the Great Spirit has made, from the highest mountain to the smallest stone, as worthy of their idolatry.

They have a vague idea of a future state; many have dreamed of it. Some of their medicine men pretend to have had revelations from bears and other animals; and they thus learned that their future existence would be but a continuation of this. They will go on long hunts and kill many buffalo; bright fires will burn in their wigwams as they talk through the long winter's night of the traditions of their ancients; their women are to tan deer-skin for their mocassins, while their young children learn to be brave warriors by attacking and destroying wasps' or hornets' nests; they will celebrate the dog feast to show how brave they are, and sing in triumph as they dance round the scalps of their enemies. Such is the Heaven of the Dakotas! Almost every Indian has the image of an animal or bird tattooed on his breast or arm, which can charm away an evil spirit, or prevent his enemy from bringing trouble or death upon him by a secret shot. The power of life rests with mortals, especially with their medicine men; they believe that if an enemy be shooting secretly at them, a spell or charm must be put in requisition to counteract their power.

The medicine men or women, who are initiated into the secrets of their wonderful medicines, (which secret is as sacred with them as free-masonry is to its members) give the feast which they call the medicine feast.

Their medicine men, who profess to administer to the affairs of soul and body are nothing more than jugglers, and are the worst men of the tribe: yet from fear alone they claim the entire respect of the community.

There are numerous clans among the Dakotas each using a different medicine, and no one knows what this medicine is but those who are initiated into the mysteries of the medicine dance, whose celebration is attended with the utmost ceremony.

A Dakota would die before he would divulge the secret of his clan. All the different clans unite at the great medicine feast.

And from such errors as these must the Dakota turn if he would be a Christian! And the heart of the missionary would faint within him at the work which is before him, did he not remember who has said "Lo, I am with you always!"

And it was long before the Indian woman could give up the creed of her nation. The marks of the wounds in her face and arms will to the grave bear witness of her belief in the faith of her fathers, which influenced her in youth. Yet the subduing of her passions, the quiet performance of her duties, the neatness of her person, and the order of her house, tell of the influence of a better faith, which sanctifies the sorrows of this life, and rejoices her with the hope of another and a better state of existence.

But such instances are rare. These people have resisted as encroachments upon their rights the efforts that have been made for their instruction. Kindness and patience, however, have accomplished much, and during the last year they have, in several instances, expressed a desire for the aid and instructions of missionaries. They seem to wish them to live among them; though formerly the lives of those who felt it their duty to remain were in constant peril.

They depend more, too, upon what the ground yields them for food, and have sought for assistance in ploughing it.

There are four schools sustained by the Dakotas mission; in all there are about one hundred and seventy children; the average attendance about sixty.

The missionaries feel that they have accomplished something, and they are encouraged to hope for still more. They have induced many of the Dakotas to be more temperate; and although few, comparatively, attend worship at the several stations, yet of those few some exhibit hopeful signs of conversion.

There are five mission stations among the Dakota; at "Lac qui parle," on the St. Peter's river, in sight of the beautiful lake from which the station takes its name; at "Travers des Sioux" about eighty miles from Fort Snelling; at Xapedun, Oak-grove, and Kapoja, the last three being within a few miles of Fort Snelling.

There are many who think that the efforts of those engaged in instructing the Dakotas are thrown away. They cannot conceive why men of education, talent, and piety, should waste their time and attainments upon a people who cannot appreciate their efforts. If the missionaries reasoned on worldly principles, they would doubtless think so too; but they devote the energies of soul and body to Him who made them for His own service.

They are pioneers in religion; they show the path that others will walk in far more easily at some future day; they undertake what others will carry on,—what God himself will accomplish. They have willingly given up the advantages of this life, to preach the gospel to the degraded Dakotas. They are translating the Bible into Sioux; many of the books are translated, and to their exertions it is owing that the praise of God has been sung by the children of the forest in their own language.