The Cherokee Indian Mound Builders of Tennessee and North Carolina

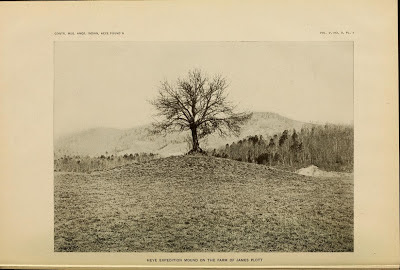

Cherokee Indian Burial Mound in North Carolina. Most of these mounds have been desecrated by university archaeologist

As the evidence on this point has to a large extent been presented in my article on "Burial Mounds of the Northern Section," [Footnote: Fifth Ann. Rept. Bur Ethnol] also in articles published in the Magazine of American History [Footnote: May, 1884, pp. 396- 407] and in the American Naturalist, [Footnote: Vol. 18, 1884, pp. 232-240] it will be necessary here only to introduce a few additional items.

The iron implements which are alluded to in the above mentioned articles also in Science, [Footnote: Science, vol. 3, 1884, pp. 308-310] as found in a North Carolina mound, and which analysis shows were not meteoric, furnish conclusive evidence that the tumulus was built after the Europeans had reached America; and as it is shown in the same article that the Cherokees must have occupied the region from the time of its discovery up to its settlement by the whites it is more than probable they were the builders. A figure of one of the pieces is introduced here.

Additional and perhaps still stronger evidence, if stronger be needed, that the people of this tribe were the authors of most of the ancient works in western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee is to be found in certain discoveries made by the Bureau assistants in Monroe County, Tenn.

A careful exploration of the valley of the Little Tennessee River, from the point where it leaves the mountains to its confluence with the Holston, was made, and the various mound groups were located and surveyed. These were found to correspond down as far as the position of Fort London and even to the island below with the arrangement of the Cherokee "over-hill towns" as given by Timberlake in his map of the Cherokee country called "Over the Hills," [Footnote: Memoirs, 1765] a group for each town, and in the only available spots the valley for this distance affords. As these mounds when explored yielded precisely the kind of ornaments and implements used by the Cherokees, it is reasonable to believe they built them.

Ramsey also gives a map, [Footnote: Annals of Tennessee, p. 376] but his list evidently refers to a date corresponding with the close of their occupancy of this section. Bartram [Footnote: Travels, pp. 373.374.] gives a more complete list applying to an earlier date. This evidently includes some on the Holston (his "Cherokee") River and some on the Tellico plains. This corresponds precisely with the result of the explorations by the Bureau as will be seen when the report is published. Some three or four groups were discovered in the region of Tellico plains, and five or six on the Little Tennessee below Fort London and on the Holston near the junction, one large mound and a group being on the "Big Island" mentioned in Bartram's list.

The largest of these groups is situated on the Little Tennessee above Fort London and corresponds with the position of the ancient "beloved town of Chota" ("Great Chote" of Bartram) as located by tradition and on both Timberlake's and Ramsey's maps. According to Ramsey, [Footnote: Annals of Tennessee, p. 157] at the time the pioneers, following in the wake of Daniel Boone near the close of the eighteenth century, were pouring over the mountains into the valley of the Watauga, a Mrs. Bean, who was captured by the Cherokees near Watauga, was brought to their town at this place and was bound, taken to the top of one of the mounds and about to be burned, when Nancy Ward, then exercising in the nation the functions of the Beloved or Pretty Woman, interfered and pronounced her pardon.

During the explorations of the mounds of this region a peculiar type of clay beds was found in several of the larger mounds. These were always saucer shaped, varying in diameter from 6 to 15 feet, and in thickness from 4 to 12 inches. In nearly every instance they were found in series, one above another, with a layer of coals and ashes between. The series usually consisted of from three to five beds, sometimes only two, decreasing in size from the lower one upward. These apparently marked the stages of the growth of the mound, the upper one always being near the present surface.

The large mound which is on the supposed site of Chota, and possibly the one on which Mrs. Bean was about to be burned, was thoroughly explored, and found to contain a series of these clay beds, which always showed the action of fire. In the center of some of these were found the charred remains of a stake, and about them the usual layer of coals and ashes, but, in this instance, immediately around where the stake stood were charred fragments of human bones.

As will be seen, when the report which is now in the hands of the printer is published, the burials in this mound were at various depths, and there is nothing shown to indicate separate and distinct periods, to lead to the belief that any of these were intrusive in the true sense. On the contrary, the evidence is pretty clear that all these burials were by one tribe or people. By the side of nearly every skeleton were one or more articles, as shell masks, engraved shells, shell pins, shell beads, perforated shells, discoidal stones, polished celts, arrow-heads, spearheads, stone gorgets, bone implements, clay vessels, or copper hawkbells. The last were with the skeleton of a child found at the depth of 3 1/2 feet. They are precisely of the form of the ordinary sleigh- bell of the present day, with pebbles and shell-bead rattles.

That this child belonged to the people to whom the other burials are due will not be doubted by any one not wedded to a preconceived notion, and that the bells are the work of Europeans will also be admitted. In another mound a little farther up the river, and one of a group probably marking the site of one of the "over-hill towns," were found two carved stone pipes of a comparatively modern Cherokee type.

The next argument is founded on the fact that in the ancient works of the region alluded to are discovered evidences of habits and customs similar to those of the Cherokees and some of the immediately surrounding tribes. In the article heretofore referred to allusion is made to the evidence found in the mound opened by Professor Carr of its once having supported a building similar to the council-house observed by Bartram on a mound at the old Cherokee town Cowe. Both were built on mounds, both were circular, both were built on posts set in the ground at equal distances from each other, and each had a central pillar. As tending to confirm this statement of Bartram's, the following passage may be quoted, where, speaking of Colonel Christian's march against the Cherokee towns in 1770, Ramsey [Footnote: Annals of Tennessee, p. 169.] says that this officer found in the center of each town "a circular tower rudely built and covered with dirt, 30 feet in diameter, and about 20 feet high. This tower was used as a council-house, and as a place for celebrating the green-corn dance and other national ceremonials." In another mound the remains of posts apparently marking the site of a building were found. Mr. M. C. Read, of Hudson, Ohio, discovered similar evidences in a mound near Chattanooga, [Footnote: Smithsonian Rept, for 1867 (1868), p. 401.] and Mr. Gerard Fowke has quite recently found the same thing in a mound at Waverly. Ohio. The shell ornaments to which allusion has been made, although occasionally bearing designs which are undoubtedly of the Mexican or Central American type, nevertheless furnish very strong evidence that the mounds of east Tennessee and western North Carolina were built by the Cherokees. Lawson, who traveled through North Carolina in 1700, says [Footnote: Hist. of N. C., Raleigh, reprint 1860, p. 315.] "they [the Indians] oftentimes make of this shell [a certain large sea shell] a sort of gorge, which they wear about their neck in a string so it hangs on their collar, whereon sometimes is engraven a cross or some odd sort of figure which comes next in their fancy."

According to Adair, the southern Indian priest wore upon his breast "an ornament made of a white conch-shell, with two holes bored in the middle of it, through which he ran the ends of an otter-skin strap, and fastened to the extremity of each, a buck- horn white button." [Footnote: Hist. Am. Indians, p. 84]

Beverly, speaking of the Indians of Virginia, says: "Of this shell they also make round tablets of about 4 inches in diameter, which they polish as smooth as the other, and sometimes they etch or grave thereon circles, stars, a half-moon, or any other figure suitable to their fancy." [Footnote: Hist. Virginia, London, 1705, p. 58]

Now it so happens that a considerable number of shell gorgets have been found in the mounds of western North Carolina and east Tennessee, agreeing so closely with those brief descriptions, as may be seen the figures of some of them given here (see Figs. 2 and 3), as to leave no doubt that they belong to the same type as those alluded to by the writers whose words have just been quoted. Some of them were found in the North Carolina mound from which the iron articles were obtained and in connection with these articles. Some of these shells were smooth and without any devices engraved upon them, but with holes for inserting the strings by which they were to be held in position; others were engraved with figures, which, as will be seen by reference to the cuts referred to, might readily be taken for stars and half-moons, and one among the number with a cross engraved upon it.The evidence that these relics were the work of Indians found in possession of the country at the time of its discovery by Europeans, is therefore too strong to be put aside by mere conjectures or inferences. If they were the work of Indians, they must have been used by the Cherokees and buried with their dead. It is true that some of the engraved figures present a puzzling problem in the fact that they bear unmistakable evidences of pertaining to Mexican and Central American types, but no explanation of this which contradicts the preceding evidences that these shells had been in the hands of Indians can be accepted.

In these mounds were also found a large number of nicely carved soapstone pipes, usually with the stem made in connection with the bowl, though some were without this addition, consisting only of the bowl with a hole for inserting a cane or wooden stem. While some, as will hereafter be shown, closely resemble one of the ancient Ohio types, others are precisely of the form common a few years back, and some of them have the remains of burnt tobacco yet clinging to them.

Adair, in his "History of the North American Indians," [Footnote:

P. 433.] says:

"They mate beautiful stone pipes and the Cherokees the best of any of the Indians, for their mountainous country contain many different sorts and colors of soils proper for such uses. They easily form them with their tomahawks and afterwards finish them in any desired form with their knives, the pipes being of a very soft quality till they are smoked with and used with the fire, when they become quite hard. They are often full a span long and the bowls are about half as large again as our English pipes. The fore part of each commonly runs out with a sharp peak 2 or 3 fingers broad and a quarter of an inch thick."

Not only were pipes made of soapstone found in these mounds, but two or three were found precisely of the form mentioned by Adair, with the fore part running out in front of the bowl (see Fig. 5, p. 39).

It has been more than hinted at by at least one person whose statement is entitled to every belief, that among the Cherokees dwelling in the mountains there existed certain artists whose professed occupation was the manufacture of stone pipes, which were by them transported to the coast and there bartered away for articles of use and ornament foreign to and highly esteemed among the members of their own tribe.

This not only strengthens the conclusions drawn from the presence of such pipes in the mounds alluded to, but may also assist in explaining the presence of the copper and iron ornaments in them.

During the fall of 1886 a farmer of east Tennessee while examining a cave with a view to storing potatoes in it during the winter unearthed a well preserved human skeleton which was found to be wrapped in a large piece of cane matting. This, which measures about 6 by 4 feet, with the exception of a tear at one corner is perfectly sound and pliant and has a large submarginal stripe running around it. Inclosed with the skeleton was a piece of cloth made of flax, about 14 by 20 inches, almost uninjured but apparently unfinished. The stitch in which it is woven is precisely that imprinted on mound pottery of the type shown in Fig. 96 in Mr. Holmes's paper on the mound-builders' textile fabrics reproduced here in Fig. 4. [Footnote: Fifth Ann. Rept. Bur. Ethnol., p. 415, Fig. 96.]

Although the earth of the cave contains salts which would aid in preserving anything buried in it, these articles can not be assigned to any very ancient date, especially when it is added that with them were the remains of a dog from which the skin had not all rotted away.

These were presumably placed here by the Cherokees of modern times, and they form a link not easily broken between the prehistoric and historic days.

It is probable that few persons after reading this evidence will doubt that the mounds alluded to were built by the Cherokees. Let us therefore see to what results this leads.

In the first place it shows that a powerful and active tribe in the interior of the country, in contact with the tribes of the North on one side and with those of the South on the other, were mound-builders. It is reasonable to conclude, therefore, that they had derived this custom from their neighbors on one side or the other, or that they had, to some extent at least, introduced it among them. Beyond question it indicates that the mound-building era had not closed previous to the discovery of the continent by Europeans. [Footnote: Since the above was in type one of the assistants of the Ethnological Bureau discovered in a small mound in east Tennessee a stone with letters of the Cherokee alphabet rudely carved upon it. It was not an intensive burial, hence it is evident that the mound must have been built since 1820, or that Guess was not the author of the Cherokee alphabet.]

Cherokee Photo PageCherokee Indian Pictures Here