The Iroquois Indians Myth of the Great Head and the Ten Brothers

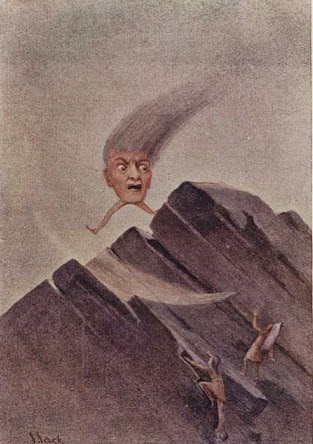

It was commonly believed among the Iroquois Indians that there existed a curious and malevolent being whom they called Great Head. This odd creature was merely an enormous head poised on slender legs. He made his dwelling on a rugged rock, and directly he saw any living person approach he would growl fiercely in true ogre fashion: "I see thee, I see thee! Thou shalt die."

Far away in a remote spot an orphaned family of ten boys lived with their uncle. The older brothers went out every day to hunt, but the younger ones, not yet fitted for so rigorous a life, remained at home with their uncle, or at least did not venture much beyond the immediate vicinity of their lodge. One day the hunters did not return at their usual hour. As the evening passed without bringing any sign of the missing

youths the little band at home became alarmed. At length the eldest of the boys left in the lodge volunteered to go in search of his brothers. His uncle consented, and he set off, but he did not return.

In the morning another brother said: "I will go to seek my brothers." Having obtained permission, he went, but he also did not come back. Another and another took upon himself the task of finding the lost hunters, but of the searchers as well as of those sought for there was no news forthcoming. At length only the youngest of the lads remained at home, and to his entreaties to be allowed to seek for his brothers the uncle turned a deaf ear, for he feared to lose the last of his young nephews.

One day when uncle and nephew were out in the forest the latter fancied he heard a deep groan, which seemed to proceed from the earth exactly under his feet. They stopped to listen. The sound was repeated—unmistakably a human groan. Hastily they began digging in the earth, and in a moment or two came upon a man covered with mould and apparently unconscious.

The pair carried the unfortunate one to their lodge, where they rubbed him with bear's oil till he recovered consciousness. When he was able to speak he could give no explanation of how he came to be buried alive. He had been out hunting, he said, when suddenly his mind became a blank, and he remembered nothing more till he found himself in the lodge with the old man and the boy. His hosts begged the stranger to stay with them, and they soon discovered that he was no ordinary mortal, but a powerful magician. At times he behaved very strangely. One night, while a great storm raged without, he tossed restlessly on his couch instead of going to sleep. At last he sought the old uncle.

Do you hear that noise?" he said. "That is my brother, Great Head, who is riding on the wind. Do you not hear him howling?"

The old man considered this astounding speech for a moment; then he asked: "Would he come here if you sent for him?"

"No," said the other, thoughtfully, "but we might bring him here by magic. Should he come you must have food ready for him, in the shape of huge blocks of maple-wood, for that is what he lives on."

The stranger departed in search of his brother Great Head, taking with him his bow, and on the way he came across a hickory-tree, whose roots provided him with arrows. About midday he drew near to the dwelling of his brother, Great Head. In order to see without being seen, he changed himself into a mole, and crept through the grass till he saw Great Head perched on a rock, frowning fiercely. "I see thee!" he growled, with his wild eyes fixed on an owl. The man-mole drew his bow and shot an arrow at Great Head. The arrow became larger and larger as it flew toward the monster, but it returned to him who had fired it, and as it did so it regained its natural size. The man seized it and rushed back the way he had come. Very soon he heard Great Head in pursuit, puffing and snorting along on the wings of a hurricane. When the creature had almost overtaken him he turned and discharged another arrow. Again and again he repulsed his pursuer in this fashion, till he lured him to the lodge where his benefactors lived. When Great Head burst into the house the uncle and nephew began to hammer him vigorously with mallets. To their surprise the monster broke into laughter, for he had recognized his brother and was very pleased to see him. He ate the maple-blocks they brought him with a

hearty appetite, whereupon they told him the story of the missing hunters.

"I know what has become of them," said Great Head. "They have fallen into the hands of a witch. If this young man," indicating the nephew, "will accompany me, I will show him her dwelling, and the bones of his brothers."

The youth, who loved adventure, and was besides very anxious to learn the fate of his brothers, at once consented to seek the home of the witch. So he and Great Head started off, and lost no time in getting to the place. They found the space in front of the lodge strewn with dry bones, and the witch sitting in the doorway singing. When she saw them she muttered the magic word which turned living people into dry bones, but on Great Head and his companion it had no effect whatever. Acting on a prearranged signal, Great Head and the youth attacked the witch and killed her. No sooner had she expired than her flesh turned into birds and beasts and fishes. What was left of her they burned to ashes.

Their next act was to select the bones of the nine brothers from among the heap, and this they found no easy task. But at last it was accomplished, and Great Head said to his companion: "I am going home to my rock. When I pass overhead in a great storm I will bid these bones arise, and they will get up and return with you."

The youth stood alone for a little while till he heard the sound of a fierce tempest. Out of the hurricane Great Head called to the brothers to arise. In a moment they were all on their feet, receiving the congratulations of their younger brother and each other, and filled with joy at their reunion.

Far away in a remote spot an orphaned family of ten boys lived with their uncle. The older brothers went out every day to hunt, but the younger ones, not yet fitted for so rigorous a life, remained at home with their uncle, or at least did not venture much beyond the immediate vicinity of their lodge. One day the hunters did not return at their usual hour. As the evening passed without bringing any sign of the missing

youths the little band at home became alarmed. At length the eldest of the boys left in the lodge volunteered to go in search of his brothers. His uncle consented, and he set off, but he did not return.

In the morning another brother said: "I will go to seek my brothers." Having obtained permission, he went, but he also did not come back. Another and another took upon himself the task of finding the lost hunters, but of the searchers as well as of those sought for there was no news forthcoming. At length only the youngest of the lads remained at home, and to his entreaties to be allowed to seek for his brothers the uncle turned a deaf ear, for he feared to lose the last of his young nephews.

One day when uncle and nephew were out in the forest the latter fancied he heard a deep groan, which seemed to proceed from the earth exactly under his feet. They stopped to listen. The sound was repeated—unmistakably a human groan. Hastily they began digging in the earth, and in a moment or two came upon a man covered with mould and apparently unconscious.

The pair carried the unfortunate one to their lodge, where they rubbed him with bear's oil till he recovered consciousness. When he was able to speak he could give no explanation of how he came to be buried alive. He had been out hunting, he said, when suddenly his mind became a blank, and he remembered nothing more till he found himself in the lodge with the old man and the boy. His hosts begged the stranger to stay with them, and they soon discovered that he was no ordinary mortal, but a powerful magician. At times he behaved very strangely. One night, while a great storm raged without, he tossed restlessly on his couch instead of going to sleep. At last he sought the old uncle.

Do you hear that noise?" he said. "That is my brother, Great Head, who is riding on the wind. Do you not hear him howling?"

The old man considered this astounding speech for a moment; then he asked: "Would he come here if you sent for him?"

"No," said the other, thoughtfully, "but we might bring him here by magic. Should he come you must have food ready for him, in the shape of huge blocks of maple-wood, for that is what he lives on."

The stranger departed in search of his brother Great Head, taking with him his bow, and on the way he came across a hickory-tree, whose roots provided him with arrows. About midday he drew near to the dwelling of his brother, Great Head. In order to see without being seen, he changed himself into a mole, and crept through the grass till he saw Great Head perched on a rock, frowning fiercely. "I see thee!" he growled, with his wild eyes fixed on an owl. The man-mole drew his bow and shot an arrow at Great Head. The arrow became larger and larger as it flew toward the monster, but it returned to him who had fired it, and as it did so it regained its natural size. The man seized it and rushed back the way he had come. Very soon he heard Great Head in pursuit, puffing and snorting along on the wings of a hurricane. When the creature had almost overtaken him he turned and discharged another arrow. Again and again he repulsed his pursuer in this fashion, till he lured him to the lodge where his benefactors lived. When Great Head burst into the house the uncle and nephew began to hammer him vigorously with mallets. To their surprise the monster broke into laughter, for he had recognized his brother and was very pleased to see him. He ate the maple-blocks they brought him with a

hearty appetite, whereupon they told him the story of the missing hunters.

"I know what has become of them," said Great Head. "They have fallen into the hands of a witch. If this young man," indicating the nephew, "will accompany me, I will show him her dwelling, and the bones of his brothers."

The youth, who loved adventure, and was besides very anxious to learn the fate of his brothers, at once consented to seek the home of the witch. So he and Great Head started off, and lost no time in getting to the place. They found the space in front of the lodge strewn with dry bones, and the witch sitting in the doorway singing. When she saw them she muttered the magic word which turned living people into dry bones, but on Great Head and his companion it had no effect whatever. Acting on a prearranged signal, Great Head and the youth attacked the witch and killed her. No sooner had she expired than her flesh turned into birds and beasts and fishes. What was left of her they burned to ashes.

Their next act was to select the bones of the nine brothers from among the heap, and this they found no easy task. But at last it was accomplished, and Great Head said to his companion: "I am going home to my rock. When I pass overhead in a great storm I will bid these bones arise, and they will get up and return with you."

The youth stood alone for a little while till he heard the sound of a fierce tempest. Out of the hurricane Great Head called to the brothers to arise. In a moment they were all on their feet, receiving the congratulations of their younger brother and each other, and filled with joy at their reunion.